"Going out of the classroom setting to build human connections with people who have a very different experience from me and really hear their voices was the most meaningful part of the course,” wrote Yinghong Ding '25 in a reflection on her January Term experience. “I realize that any grand vision begins with a genuine connection between individuals.”

The winter break flew by, but eleven J Term students studying with Dr. Zhang Liangliang, postdoctoral teaching fellow for Global Perspectives on Society (GPS) and incoming assistant professor for Global China Studies (Fall 2024), dove deep into everyday life and education in rural Guangdong Province by learning community-engaged ethnography and then carrying out their own fieldwork-based projects in research teams.

Dr. Zhang’s project-driven Experience Studio course, Making a “Good Education” for Migrant Children in Rural Guangdong Province, was designed to help students explore how to practice community-engaged ethnographic fieldwork in a real-life scenario. The course is a collaboration with NYU Shanghai’s Community Engaged Learning (CEL) program, Guinan School, and Kei Kai Ecological Community, who Zhang has established partnerships with through her own research and community engagement.

Students participating in a community-engaged action research Workshop: Co-Creating Family Support Action Plan, co-facilitated by Kei Kai Community Partner/New Villager Xu Qi and Zhang

The group traveled to the small village of Kei Kai, where they spent the next twelve days getting to know this multi-layered community, with a focus on building connections with the children, school leaders, families, and other stakeholders of Guinan School–an innovative privately run primary and middle school supporting 1,200 students, mostly children of rural migrant workers.

In 2022, more than half of the students who graduated from Guinan went on to vocational high schools, while about 35% entered regular high schools, and 5% stopped receiving formal education.The NYU Shanghai students’ fieldwork used Guinan School as a case study to explore how grassroots privately run schools can provide a “good education” for migrant children.

At the crux of that issue were two questions the students delved into, invited by the school leadership: What do families really think about their children’s education and how do teachers really feel about their jobs?

Students participating in a walking meditation in the bamboo forests of Kei Kai Herbal Living Farm, led by Community Partner/New Villager Yang Xiangruo

Over the course of twelve days, the students immersed themselves in the village community and the school, toured the village, visited farms, held numerous formal and informal conversations with diverse stakeholders, shadowed the school principals, and developed deep relationships with select teachers and student families to learn more about the possibilities and challenges of education in rural China.

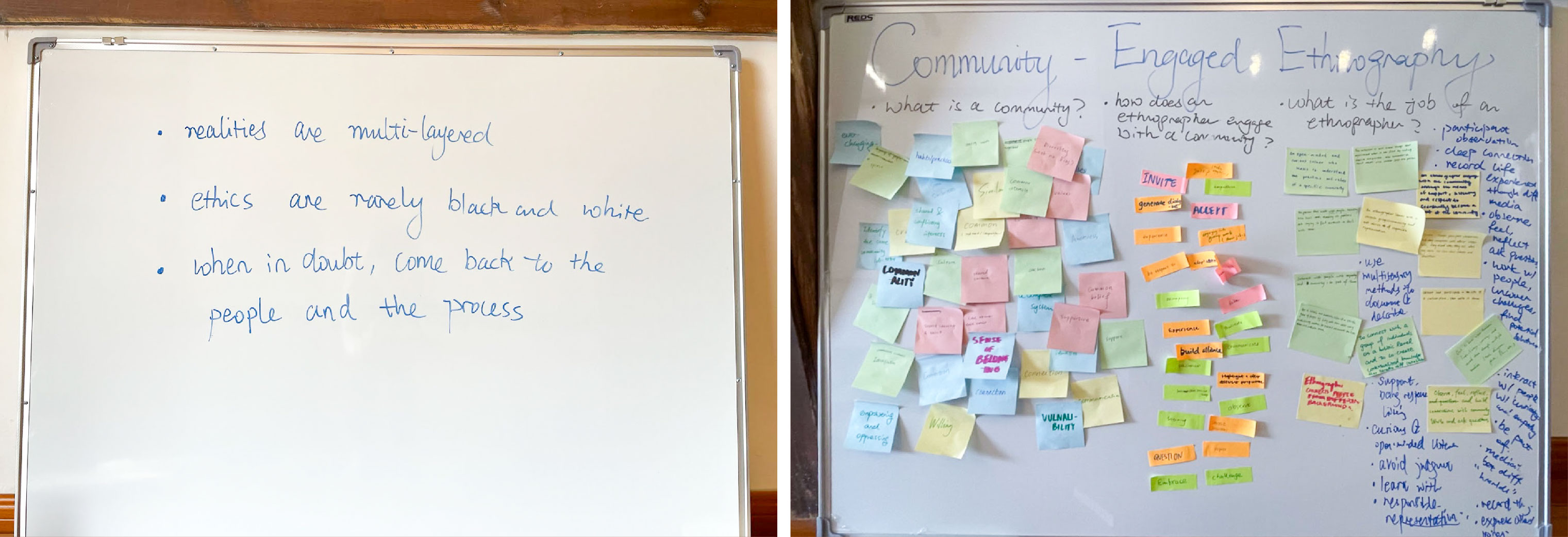

Left: Zhang introduced three principles to guide her class throughout their research: “Realities are multi-layered; ethics are rarely black-and-white; when in doubt, come back to people and processes.” Right: The entire team co-created a vision board using sticky notes to collage their responses to questions about community and the job of ethnographers.

Even within such a short timeframe, Zhang wanted to support her students to experience the day-to-day life of being a community-engaged ethnographer. “It was a lot for them to handle,” she said. “They were challenged, but they also had outlets to process the cognitive and emotional dissonances as an individual and on the group level.” She worked to build each student’s confidence by showing more vulnerability, being open and honest about the challenges she was facing in the field alongside the students, and encouraging students to share their emerging observations and voice their work-in-progress ideas.

Holding an informal ethnographic interview with two young urban-to-rural migrants in Kei Kai Ecological Farm

She also wanted to empower students to experience collaborative research and work as equal members of a research team. The students worked together in teams of two to three to practice participant observation and qualitative interviews. They learned community-engaged facilitation techniques from experienced community facilitator Xu Qi, who played a key role throughout the course and enriched the instructional capacity by providing a fresh perspective. Furthermore, using their newly gained community-engaged ethnographic research and facilitation skills, and with the support of Zhang, Xu, and course chaperone CEL Coordinator Qian Chunhao, students participated in the ideation, design, and implementation of two full-day collaborative research experiences.

First, students and faculty collaborated with Guinan School families and teacher representatives to foster family communication and create family support action plans. Students and faculty then engaged teacher representatives in experiential dialogues and rapport building through a half-day hike. They supported teachers in a collaborative workshop aimed to foster genuine communication between frontline teachers and school leadership and enable them to generate a shared educational vision.

Left: NYU New York study away student Alesia Zhou ’26 sharing her most memorable finding with all stakeholders during the community-engaged action research workshop: “Co-Creating Family Support Action Plan.” Right: Students supporting Guinan School teacher representatives and conducting participant observation during the community-engaged action research workshop: “Co-Creating Teachers’ Education Vision.”

Having a community-engaged facilitation workshop in Xu Qi’s living room – In Kei Kai, the classroom can take on many shapes and spaces

Everyday, Zhang encouraged the students to observe, reflect on, and challenge their own assumptions. She brought the students together in frequent sharing circles, where they connected with each other and shared their experiences.

“I was amazed by how ingenious and invaluable their insights were,” Zhang said. It was important, she said, for the students to build trust and holistic relationships among themselves as well as with the greater community that they were engaging and serving. Zhang said watching students learn to connect on a human level with the villagers, school staff, and parents was one of the most rewarding aspects of the class.

But it wasn’t without challenges. When students struggled facing conflictual information and perspectives that challenged their own, Zhang had to resist the impulse to step in while still providing space and guidance for students to process and evolve their thinking over time.

Siripakorn and Hao presenting their project at the community research sharing event hosted on Guinan School campus

At the end of the two-week course, the five teams presented their final projects to over 40 community stakeholders including school leadership, teachers, families, and Kei Kai Ecological Community members, addressing a variety of community needs identified through ethnographic research, including improving student-family communication, supporting children’s emotional communication, helping teachers improve their interpersonal relationships, mobilizing Kei Kai community partners to support Guinan families, and helping parents understand the school’s education philosophy.

In their final project, Pitchakorn Siripakorn ’25 and his teammate Hao Shan ’26 pitched ideas for reframing the school’s parent-teacher conference, suggesting that introducing basic facilitation techniques and adopting an active listening style would encourage parents to speak up and get more involved. “We realized that most families have no clue what their kids are up to in school, while the homeroom teacher knows so much more."

Dipping their toes into community-engaged ethnographic research left a deep impression on the students. Siripakorn says he believes a good education lies in a meaningful connection between learner and teacher. “Overall, I think that it is the best class at NYU Shanghai, and I hope we have more immersive and experimental place-based courses like this one in the future!”

Zhang said that the course had achieved her aim of giving students a crash course in community-engaged ethnographic fieldwork. “Their beautiful ideals regarding ‘community’ and ‘community-engaged ethnography’ went out the window as they realized how difficult and fragmentary these concepts and practices are,” she said. “They were able to walk away with a rare and realistic understanding of what it feels like to do this kind of work.”

“However,” she added, “I am glad that none of these difficulties prevented students from appreciating the rewards of collaborative research and the generative potential of building connections across differences.”