NYU Shanghai Professor of Neuroscience and Psychology Li Li’s career has taken her from Lanzhou to Beijing to Rhode Island to Hong Kong. She’s worked in academia, NASA, and the private sector, all while raising two daughters. Recently, she sat down to look back on her journey so far across continents and industries - and share how she found her way back to academia and to Shanghai.

You started your academic career as a psychology major at Peking University (PKU). How did you settle on neuroscience as your field of study?

I followed a very typical growth path of a good Chinese student back in high school in Lanzhou, Gansu, where I was good at taking exams and got a good grade on the gaokao [the national college entrance exams] to get into PKU. When deciding my major, I picked psychology as it seemed most interesting and could provide me with opportunities to interact with people.

Psychology has many sub areas, and I felt most interested in using experimental and computational methods to study rules and mechanisms underlying our cognition, which is also known as Cognitive Psychology. I still remember the shock I experienced when, for the first time, I entered the Perception and Action Lab at Brown University about 20 years ago. The visual displays and virtual reality techniques researchers in the lab were using to conduct scientific experiments to expand the boundaries of knowledge with so much passion made me say, “wow, this is so cool!”

Left: Li at Brown University in the 1990s; Right: Li at her PhD commencement

As a typical “science person,” the most attractive aspect of scientific research for me is that it allows “data to speak for themselves.” I initially focused on memory and representation, but later on, I found that it was not strongly driven by data in many ways. So, I shifted my focus to perception and action. I enjoy using scientific methodologies to study brains and feel obsessed with the beauty of the logic, preciseness, and scientificity of research. I’m always in search of keys to unaddressed questions through research.

You’ve worked in both academia and industry. How did you finally settle on university research and teaching as your life’s work?

After obtaining my PhD from Brown University and working as a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School, I gradually lost confidence in my career as an academic. I could foresee the entire career path, which lacked surprises and dampened my enthusiasm. I wanted to explore more possibilities, so I went to industry.

I worked as a human factors scientist at an engineering and scientific consulting firm in the Bay Area of California. But I soon became bored with the simple and repetitive procedural work I was assigned to do everyday. More importantly, I felt my graduate and postdoctoral training was wasted. Though the university salary was not as competitive as that in the industry, I realized that my true joy comes from figuring out the essence of the world and deciphering the mystery of the brain.

While making all these job shifts, I constantly asked myself what on earth I was working for. Did I work for intellectual challenges or monetary reward? The majority of people will choose to go into industry, leaving only a small group of people who can endure loneliness to stick to research. I eventually realized that the “lonely” research path fits me better.

Since joining NYU Shanghai, you’ve spent a lot of time and effort on building three different labs. Could you tell us more about them?

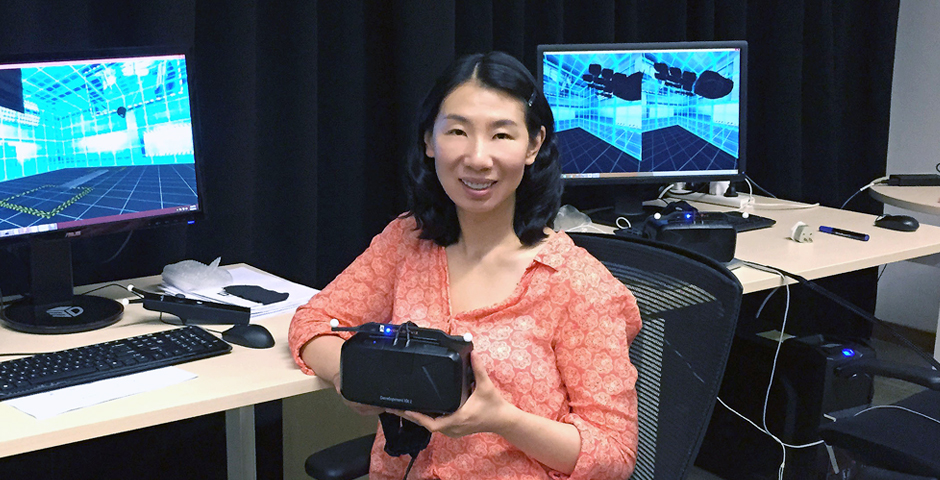

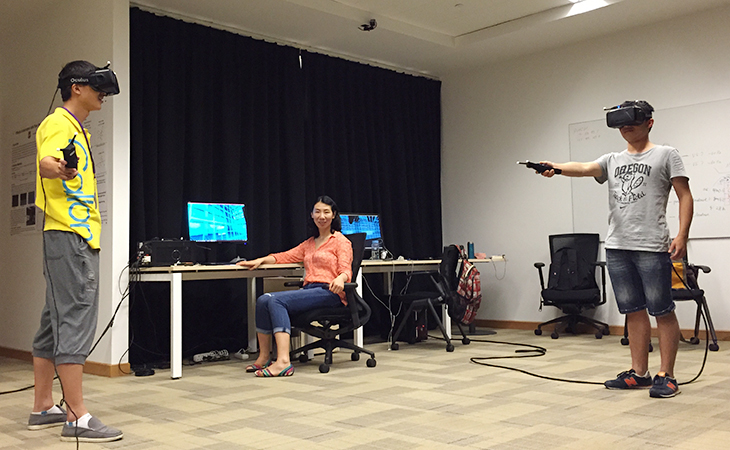

The first lab, known as the Perception and Action Virtual Reality Lab, focuses on using the virtual reality techniques to study perception, control of self-motion, and eye-hand coordination. The second lab is the Perception and Action Neural Mechanism Lab which focuses on examining the related underlying neural mechanisms. The third lab is the Neuropsychology Lab at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital. We study visuomotor and locomotion control in patients with neurodegenerative motor deficits such as Parkinson’s Disease.

Recently, we conducted a series of fMRI experiments and identified the areas of the brain where motion and form information are integrated for the perception of self-motion. We also examined baseball players’ basic visuomotor abilities and found that their basic eye tracking ability could predict their potentials in hitting baseballs. Moreover, we discovered the impairment of visuomotor control ability and the related brain structures changes during the incubation period of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease.

Li (middle) leading experiments with VR equipment in the Perception and Action Virtual Reality Lab

As a teacher, have you found any particular skills and traits that students can cultivate to become more successful in the classroom or lab?

I’d like to share two things. First, the details are of paramount importance and play a decisive role in yielding extraordinary and great results of scientific experiments. As rigor and credibility lay the foundation for scientific research, I always ask students to pay more attention to the details, put more effort into the experimental design and the comprehension of logic, take the initiative to explore the reasons behind each step in the experiment, and prevent themselves from forgetfulness, carelessness, and taking anything for granted.

Second, long-term development in research should be supported by proficient academic writing skills. I urge my students to read more and practice their writing as much as possible so they can strengthen their sensitivity to the usage of English language and improve the logic and organization of their own writing.

Do you have advice for aspiring neuroscientists?

I think students who aim to study neuroscience should have intrinsic curiosity and thirst for knowledge about the nature of the brain. Critical thinking about the relationship between experiments and theory is also necessary. I suggest that all students who want to make a career in science never give up or give in. In all walks of life, a successful person is not always the smartest person, but certainly the one who can stick it to the end. As a perfectionist myself, I always hold an “excelsior” attitude towards work and research, and I hope that students will not be satisfied with their current situations. Only excellence can make endless progress.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

--

See more faculty spotlights on Dean Maria E. Montoya, Professor Pierre Tarrès, Professor Lena Scheen, Professor Teng Lu, Professor Guan ChengHe, Professor Guo Siyao, and Professor Zhao Lu