Assistant Professor of Global China Studies Lena Scheen arrived in Shanghai in the fall of 2013, a freshly-minted Chinese Literature PhD from Leiden University in the Netherlands and one of the first professors hired for the newly-established NYU Shanghai.

For Scheen, whose research has focused on the social and cultural impact of China’s urbanization, particularly in Shanghai, getting the chance to live and work at a global university in the city that was the subject of her research was almost 'too good to be true.’

Having spent her early academic career at Leiden, one of the world’s oldest and most tradition-bound universities, Scheen was excited to help establish and build new traditions at an institution so new that the paint on the walls was still drying when she and the first class of students arrived.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak last winter, Scheen has been staying with her parents in her hometown of Delft--a university town that has changed little since the 1500s. In a video call from her mother’s study, Scheen shared stories of daily life in her childhood home, teaching urban culture, and the imaginative power of fiction in China.

How has your daily life been since the pandemic?

I was supposed to be with my family for three weeks over the Lunar New Year, and now I've been here for half a year. The Netherlands was one of the countries that was hit very badly. My parents and I went into quarantine and didn't leave the house. Our daily routine is pretty consistent; it's very much just being inside, working on my research and doing a lot of reading.

A lot of people are complaining about not being able to go out, but I guess when you're a scholar, it's not too bad. I have more time than usual, and I also started teaching online courses. I hope to be back in China soon and jump into the craziness of a regular semester again.

How is the city of Shanghai incorporated into your research and teaching?

My research is on how China has changed so quickly in the last 30 years, focusing on the changes of Shanghai and how it has impacted society and how people have experienced those changes. But it's not just about Shanghai, it's also about asking bigger questions. Shanghai for me is a case study.

Working on contemporary Shanghai literature and having the writers living in the city where you work is amazing. I teach Shanghai Stories on Chinese literature. Every semester, I've tried to invite writers such as Chen Danyan, Wang Anyi, Xiao Bai, Mian Mian to come meet my students.

Having that access is a huge privilege. I've had several times where I hadn't planned on a writer, and I would just meet him/her at a literary event somewhere in town.

I met Xiao Bai in this way and found him sitting next to me. I just said “Hi, I'm a professor at NYU Shanghai, and my students are reading your book, would you like to come to my class?”He said, “Sure,” and two weeks later he was in my class!

Lena Scheen interviewing Shanghai local citizens. © picture by Gabby Gabriel

Why do you highlight the importance of reading fiction to your students in courses such as Shanghai Stories?

I've loved to read fiction since childhood and felt that fiction has such a value that people underestimate. People usually see it mostly as entertainment and put it on their hobby list. However, I think it does so much more.

I always tell my students, “If you really want to understand China and Shanghai, you have to read fiction.” If you want to understand the psychology of human beings, if you want to understand a different culture or society in general, fiction shows you things that scholarly texts can not.

It's because in fiction, everything is possible. You don’t need to back up everything you say with evidence such as footnotes or pure data. It's not restricted to what we don't know if we're not 100% sure and where we have all the data. It's more about how people experience things, not necessarily how they actually are.

What novel are you reading now? What are the best things you find about fiction?

I am reading an amazing novel Blossoms (繁花) by Jin Yucheng right now. Anyone who can read Chinese, I strongly recommend it to you. I always read novels several times, and you can see I wrote a lot of notes on its margins. It's written in sort of a Shanghainese Mandarin which is a unique Shanghai-style, with Shanghai expressions, Shanghai words, and Shanghai grammar in it, but it’s not Shanghainese.

It follows a couple of friends and also acquaintances from those friends throughout Shanghai history from the 60s up to the 90s. It teaches you Chinese and Shanghai history, Shanghai culture, food, architecture, literature, smells, and Shanghai sounds.

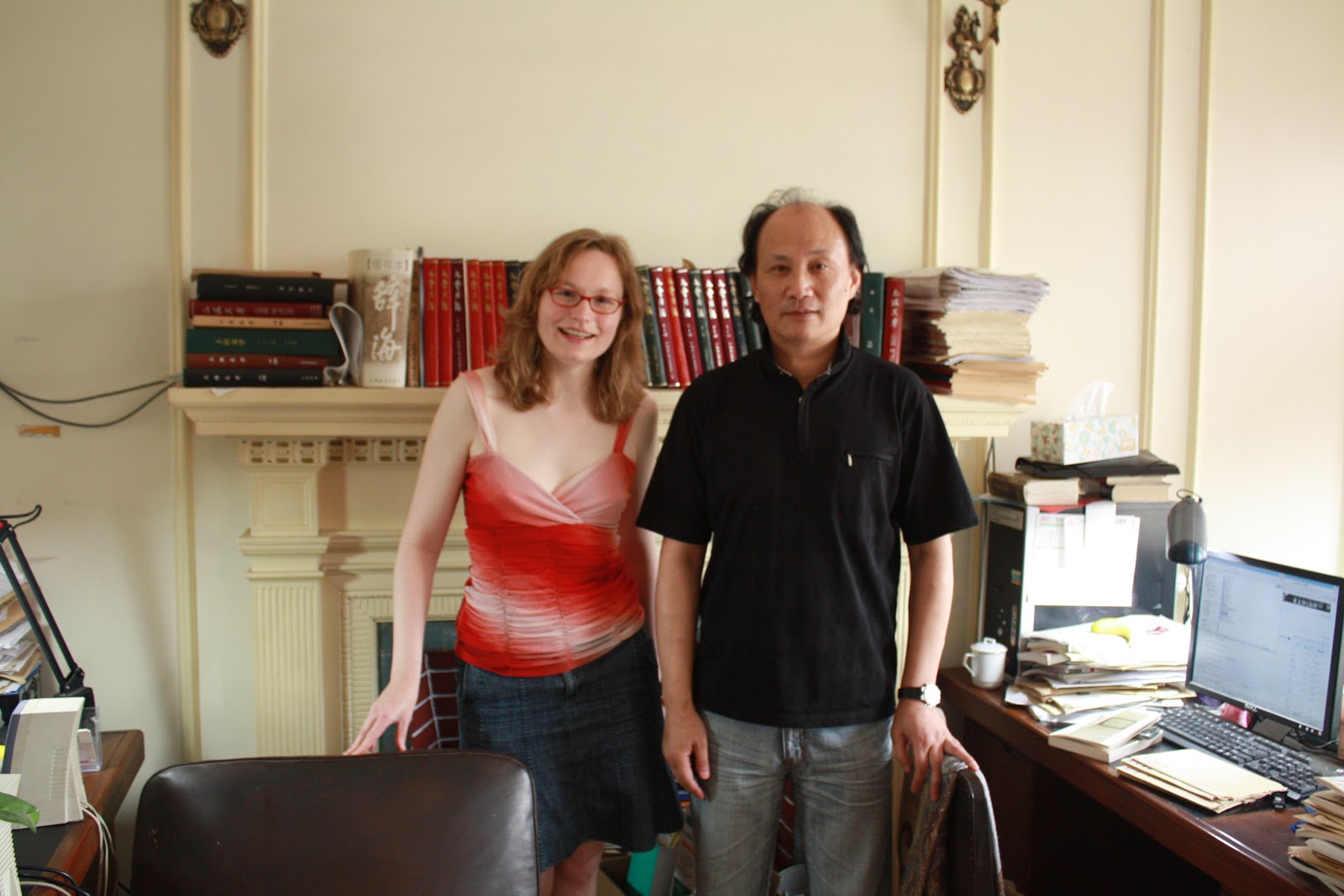

Fieldwork in Shanghai with the writer of Blossoms (繁花), Jin Yucheng (right) in his office.

Fiction can just fully immerse you in a different world without judging or analyzing. You're seeing the world through the eyes of the other person. You become the person eating the strange food and doing those 'strange things'. You don't find it strange because you are reading it from the inside perspective, while journalistic texts or scholarly texts see the world from the outsider perspective. That's what I find is the best thing about fiction.

There's actual scientific research that shows that reading fiction makes you more of an empathetic person. Reading fiction makes you more open minded and more tolerant. Without judging or analyzing, you are immersing yourself in a different world, in a different person, and that's really the power of fiction that is very much underestimated.

Is there a key component in fiction that is crucial to liberal arts education? Something that, once students acquire it, can be translated across other fields?

Imagination. Albert Einstein used to say rationality or science brings you from A to B but imagination brings you anywhere. As a scientist, he is very much aware of the importance of the imagination.

That's what fiction and creatives do. Even though we kind of know imagination is necessary in science, we don't nurture it as much. So that's what I love about teaching at NYU Shanghai, teaching at an undergrad liberal arts school that I get students not only studying Humanities or Global China Studies majors but also from science, business and finance.

If a business student wants to become a successful businessman, he needs to be a good storyteller if he wants to know which product is going to sell well but he doesn't have the data yet. He needs to imagine something that's not there yet. Imagination can help us create something totally new and better predict a blueprint for the future.

Humans need to fantasize, and we need to be able to say something crazy to at least open up the possibility of moving from where we already are. That's why I think fiction should be a required course for all students. It's important for even the most hardcore of scientists to read poetry and fiction, to sort of train their brains in moving beyond the facts and data.

What do you hope students will take away from your classes?

Of course I want students to get an understanding of Chinese literature and urban studies of Shanghai. But what I want them to take away from my class is empathy. I think it’s the root of solving all of the problems the world is facing today such as environmental issues, pandemics, the refugee crisis, and every economic crisis, etc.

No matter what majors my students choose and whatever they're going to do, I hope they will help to deal with these problems in the future and have the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. Literature is the best way to teach them empathy. When I read a novel, I feel what it's like, then I can understand something on a much deeper level that I could never do if I just heard the facts.

My secret agenda and what I really want to do is to open up students’ eyes and invite them to think about what it is like not to be them, but what it is like to be someone else.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

--

See more faculty spotlights on Dean Maria E. Montoya, Professor Pierre Tarrès, Professor Teng Lu, Professor Guan ChengHe, Professor Guo Siyao, and Professor Zhao Lu