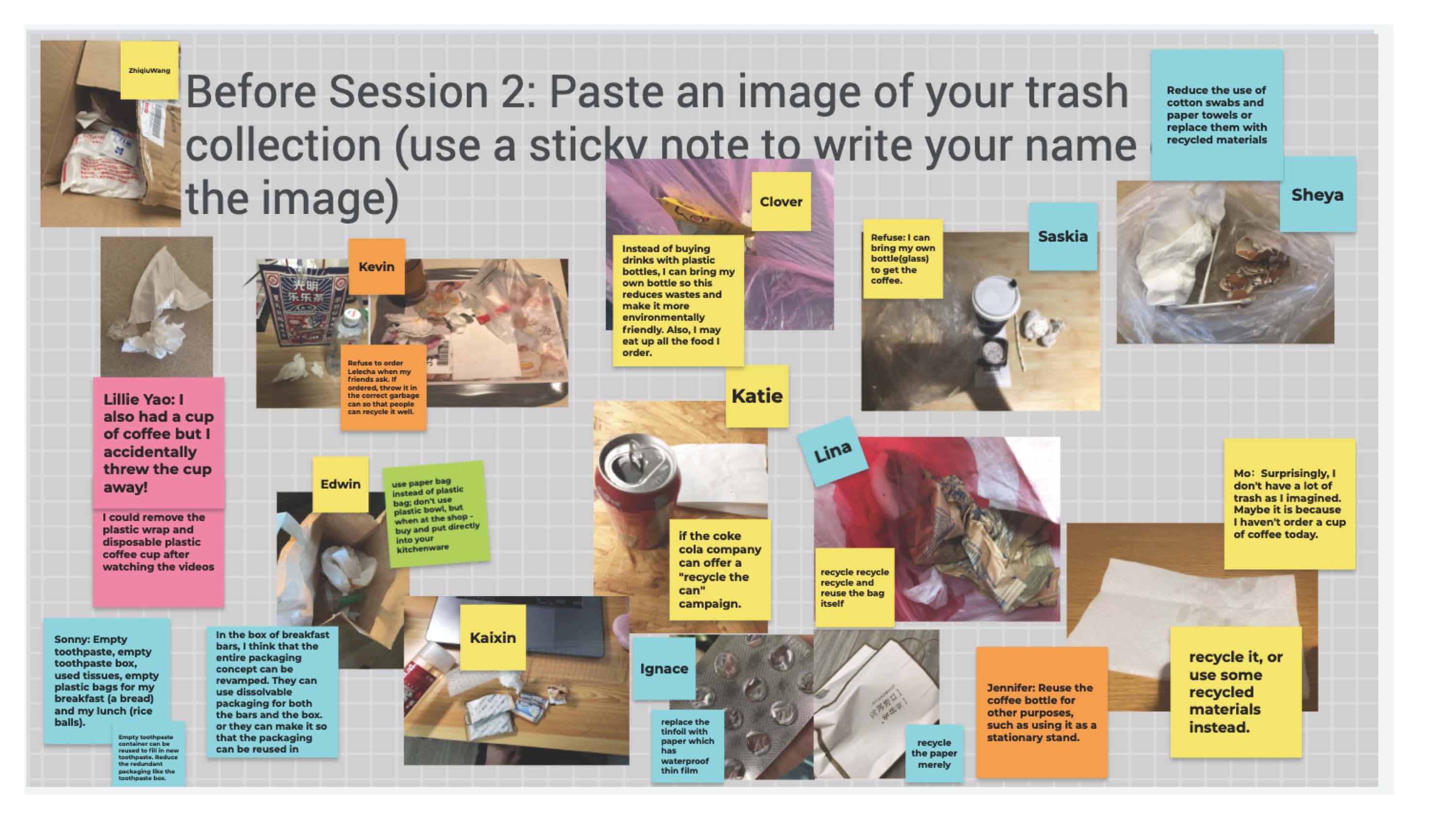

One fall afternoon, 13 students in Assistant Professor of Interactive Media Arts Yuan Yanyue’s Design Thinking class are hard at work writing on each other’s sticky notes, finding phrases to describe a random noun. Students are learning how to use chaotic data points to inspire solutions for projects designing improvements to NYU Shanghai’s “Go Local” program (see p. 3 for more on “Go Local”).

But the sticky notes aren’t exactly real. They’re virtual notes on Jamboard, a “collaborative whiteboard” app that lets students share images and text simultaneously with classmates. And the students aren’t all in the classroom – seven are in Shanghai, while the others have signed on from homes across Asia and North America.

Lillie Yao ’23, who attended Yuan’s class from Gainesville, Virginia, says Jamboard and tools like it not only ensure the quality of her distance learning experience, but also add a new dimension to class discussions and activities. “It’s a really efficient and fun way for us to communicate,” Yao says.

Yuan agrees, and she is already integrating Jamboard and other online tools into her live classes. Like Yuan, faculty across the university are finding that the tools and strategies they adopted for online classes are improving learning outcomes regardless of whether classes are live, online, or somewhere in between.

“We developed and practiced many new methods and skills due to the pandemic, and I don’t think we’re going to throw them away,” says Assistant Arts Professor of Interactive Media Arts Jung Hyun Moon, who together with IMA colleagues uses similar collaborative editing platforms like Glitch, Google Docs, and Miro to workshop student coding and multimedia projects. “I believe we are going to make them more blended and hybrid, and apply them to face-to-face teaching and learning activities as well.”

Assistant Professor of Interactive Media Arts Yuan Yanyue uses Jamboard to help students visualize how much trash they produce as part of the first step in an anti-pollution design activity.

In February 2020, when NYU Shanghai became one of the world’s first universities to move all instruction online due to COVID-19, everyone had their own doubts and fears. Over 140 faculty members were faced with an especially daunting task: How to migrate nearly 300 courses online in less than two weeks.

NYU Shanghai’s Center for Teaching and Learning, Information Technology office and Library Services provided a gauntlet of tech tools and round-the-clock emergency support, creating a “Digital Learning Toolkit” to help faculty across dozens of disciplines create the best possible distance learning experiences.

But the mission to deliver engaging courses led faculty well beyond digitally mirroring in-person classrooms. As they return to in-person teaching, NYU Shanghai instructors are using tools like asynchronous lectures (content not delivered live to the whole class at the same time), simultaneous editing platforms, and direct messaging to craft more collaborative classes and – most importantly – to restructure “classroom” time and space.

Back in the 1990s, Jace Hargis – the Center for Teaching and Learning’s director at the pandemic’s start – studied the nascent Internet’s potential to recreate the learning experiences found in aquariums, zoos, museums, and science centers. Learning online allowed students to connect more easily, with less pressure to perform. Students could also learn from a variety of media, in whatever time and context they were best prepared to learn.

“We started to realize that students learn really well in these inclusive, informal settings,” says Hargis. “And if we design our courses like one of these informal settings, then we can succeed in authentically engaging our students in multiple learning environments.”

When the all-online phase began, Yuan said she thought the biggest obstacle for her course was finding time to cover enough content. But as her experience grew, and as she began to see the results of tools like Jamboard, she realized that all along – both online and in in-person classes – the real obstacle had been building a community among her students. Online tools and activities gave students more laid-back forums for interaction, and their willingness to participate flourished.

“Students really learn from each other rather than from me,” says Yuan. “Having synchronous teaching isn’t enough to create an environment for building better relationships with students. We have to turn classes into more of a workshop.”

Even though English for Academic Purposes Lecturer Marcel Daniels now teaches all in-person classes, he is still using Flipgrid, a tool that lets students record brief speaking assignments online. The Flipgrid recordings let Daniels give feedback to each individual student, and they allow students to listen to every classmate’s response, something they couldn’t do when they were breaking out into small groups to practice. Daniels says adding the opportunity to record and replay outside of class teaches students to learn from each other’s approaches.

“It’s important for students to be able to hear the other discussions that are happening, finding the other language skills that were used there, and comparing and contrasting their abilities, skills, and techniques to one another,” Daniels says.

Adding tools like Flipgrid and Jamboard to in-person classes not only provides students with more opportunities to share ideas, but also encourages students to interact with class material in times and places outside the classroom. That’s what makes informal learning so effective: It gives learners space to relate course themes to their daily lives, leaving a deeper and longer-lasting impression than a textbook reading.

“The gaps between the times that we see each other are one of the most important aspects we can redesign when we're teaching online,” said Hargis. “What are we doing at the end of a shared class session that creates a springboard, so that the next time we see our students, we’re able to take productive conversations further?”

Chinese Language Lecturer Lu Hui-Ching says she took a cue from her students’ constant use of direct messaging app WeChat to reinforce language skills that would normally be bolstered by conversations with friends, roommates, and community members. Lu created a group chat where she shared course tips, but where she also used Chinese to ask students about their weekend plans or family and friends’ well-being, and where she shared some of her own experiences under anti-COVID restrictions.

Director of the NYU Shanghai Program on Creativity and Innovation Adam Brandenburger says he was surprised by how fruitful course discussion was when he and “Creativity Considered” co-instructor Vice Chancellor Jeff Lehman encouraged students to use group direct messaging platform Slack between classes.

As they read course materials, students used Slack to ask questions and get answers – answers from classmates as well as from Brandenburger and Lehman. Students began bringing in examples of course themes that they encountered in their own lives, posting articles and starting new discussions linking the course to their own interests and current events.

“It encourages students to be content seekers and opinion sharers in between class sections, so that the class continues even if we’re not meeting,” Brandenburger says. “That’s something that a lot of us are going to continue to do even if we’re teaching in-person courses.”

Koc Heang Lim ’23 of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, says his teachers’ use of asynchronous content delivery actually improved his overall learning ability and class participation approach.

“I was really surprised by the benefits of asynchronous learning. It took a shorter amount of time for certain tasks, and it was easier to absorb the content because I could always re-watch it again and again,” Lim says. “I found greater flexibility in how and when I study, and it led to bettering my abilities to manage my time.”

Brandenburger says pairing asynchronous content delivery with interactive class time is key to the future of the university’s mission. “We’ve all felt disconnection and loss of community during this time, so that raises the question of what universities can do post-COVID to be even better at in-person education,” he says.

“If we can move some education online, we can invest more time in mentoring and small-group discussion. That means we can significantly improve the quality of the in-person experience.”