For Associate Professor of Art History Zuo Lala, joining NYU Shanghai’s faculty in Fall 2020 was a homecoming in many ways. Not only was she returning to her hometown, she was also coming back to the country whose architecture she had spent the better part of 20 years researching from both sides of the Pacific. With its eclectic mix of buildings and spaces from many time periods and cultural traditions, Shanghai is an exciting place to explore how architecture can express changes in social structure, cultural interaction, and identity, Zuo says.

We recently joined Zuo for a visit to Shanghai’s Yu Garden, where she shared insights about this unique architectural space and about her personal journey as an architectural historian.

You grew up in Shanghai, but you spent most of the last 15 years living in the United States. How has Shanghai changed in that time, and how have those changes impacted you as a scholar?

When I finally came back and re-established my life here, I found that the city is really a new city to me. When I was in high school, there were only two subway lines, but now there are almost 20! It feels like I can go to any part of the city really, really fast. So in a way, things are also getting smaller and people are getting closer.

The changes in the city through demolishing and rebuilding old neighborhoods and old buildings have brought up a lot of issues for architectural historians. My grandparents’ house just got chai, demolished, very recently, and I visited their neighborhood for the last time in February. It's really personal to see those old neighborhoods and streets, and then imagine they're going to be gone in a few months. I think it's something emotional to a lot of people.

There's always a debate: What should we preserve, and what can we rebuild? As historians, I think we cannot just look at actual buildings or actual city planning – we should also look into people's feelings and people's memory. That has made my study of architectural history more complicated, I think.

There seems to be more and more interest in historic preservation in contemporary China. Why do you think that is the case?

In addition to the emotional aspect, I think there's another direction, which is that younger generations are trying to find some new identities, new ideas about who they are and who they will be in 21st-century China. So I think historic preservation is about seeking your own identities and your future directions. And I think it's also a global issue: How do we deal with our past?

Architecture is something we see every day. You live in architecture – it's just something that surrounds us. But we may have never thought about why a building has been built a certain way. The stories of the people behind the buildings, and how the built environment has played a role in history – especially across regions and across cultures – are really fascinating to me. In my classes, I ask my students to observe the form of the space, and what is the philosophy of power, or the political and historical aspects behind the arrangement of the space.

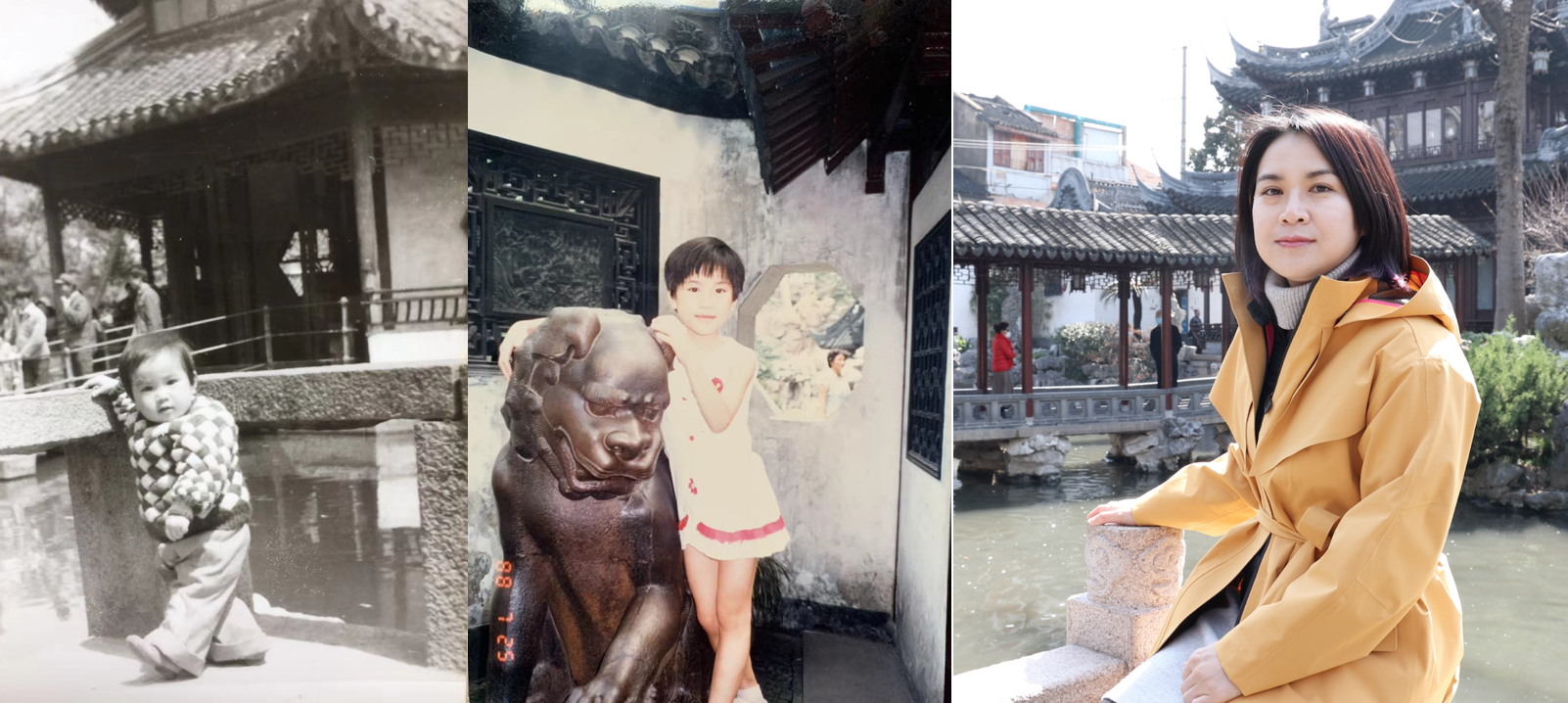

As a kid growing up in Shanghai, Zuo often visited the Yu Garden (especially the famous Huxinting Teahouse) with her family.

When did you realize that you truly had a passion for architectural history?

I was really lucky to be a member of the inaugural class of a special undergraduate program in Chinese ancient architecture at Peking University (PKU) in 1999. The fall semester of my junior year, we went on a fieldwork trip to a village in Shanxi for fifty days – I remember exactly because I really counted every day I was there! The village people invited us to a wedding, and on our way to the wedding, our professors accidentally discovered an ancient building. They identified, through certain architectural features, that this is a 10th to 11th century Jin dynasty building. No one realized it was that old before, so we actually discovered something very important historically! So that was the moment that I decided I should continue to do this in my life.

Your own research has looked at architecture in several different times and places, including regional architecture in 13th century China, 19th and 20th century gardens in the United States, and preservation mapping in World War II-era Japan. Is there a common thread that ties all these projects together?

All of my research projects examine architecture as a way for people from different cultures to communicate. For example, my current project is on Chinese architecture and gardens built in the U.S., places like the Lan Su Chinese Garden in Portland, Oregon, or the Chinese Tea House at Marble House in Newport, Rhode Island. I became interested in how architecture can be localized in a different culture. So in studying these “Chinese” spaces in the U.S., I'm examining the cultural interplay between architecture and people – how the identities of the people who have built and used these structures changed over time, and how concerns about what is “authentic” changed, too.

“Shanghai is an architectural museum,” Zuo says. “In it, we can see many sides of China – tradition, history, and modernity.” Photo by Charles Bingaman.

What drew you to NYU Shanghai, and what advice do you have for NYU Shanghai students?

In my East Asian Studies PhD cohort at the University of Pennsylvania, I got a chance to meet students from all over the world, and they studied Japanese art history, they studied Korean Buddhism, they studied literature... I realized these were all really beneficial for my studies on art and architectural history, because it is an interdisciplinary field. And we also have that kind of environment here, in NYU Shanghai’s Global China Studies program. For both my research and teaching, the most attractive thing about NYU Shanghai is that there is so little barrier between disciplines here. More importantly, now I am so close geographically to the subject that I study and teach. I look forward to taking my students on field trips throughout China.

I think it is a great opportunity that you are not set into a specific major when you’re admitted to NYU Shanghai, so there are so many things you can explore. So I would suggest to students, try to learn about something that you have never heard of before, and you never know what will turn out to work for you. So stay curious, and explore the unknown world!