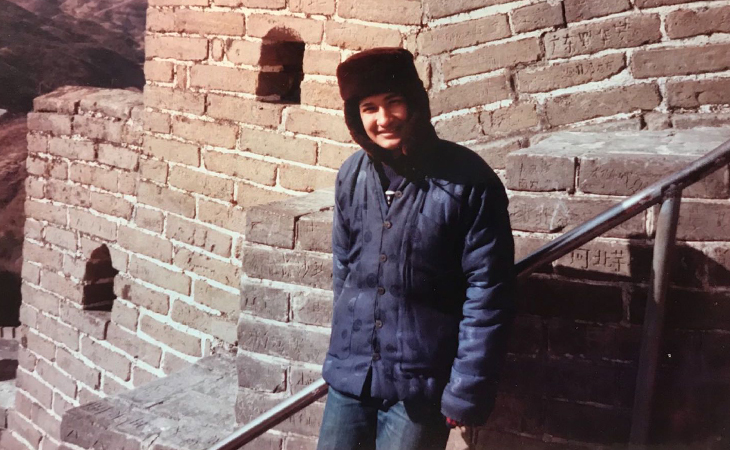

Professor of History Tansen Sen remembers his trip to China some 40 years ago. Then just 14, he had traveled to Beijing to visit his parents who were working there as translators. China’s capital city was much sleepier than Sen’s native Delhi. Very few cars traveled the streets and people dressed identically in muted military-style attire. “It was so boring,” Sen says.

Tansen Sen at the Great Wall in 1984.

But Sen eventually found much to like. When he missed bread and butter, mantou became his favorite. Ping Pong and badminton took the place of cricket and tennis. And the drab clothes and quiet streets did not last long as the era of Reform and Opening Up took off and China moved from a planned economy to a market one. “Being in China in the 1980s was fascinating,” Sen says.

At age 15, Sen became the second youngest member (after a 13-year old girl from North Korea) of his undergraduate class at what is now the Beijing Language and Culture University. It was there, and later, when he moved onto graduate studies at Peking University, that Sen discovered the materials that would become part of his life’s work -- Chinese historical records about India during the Tang and Song dynasties.

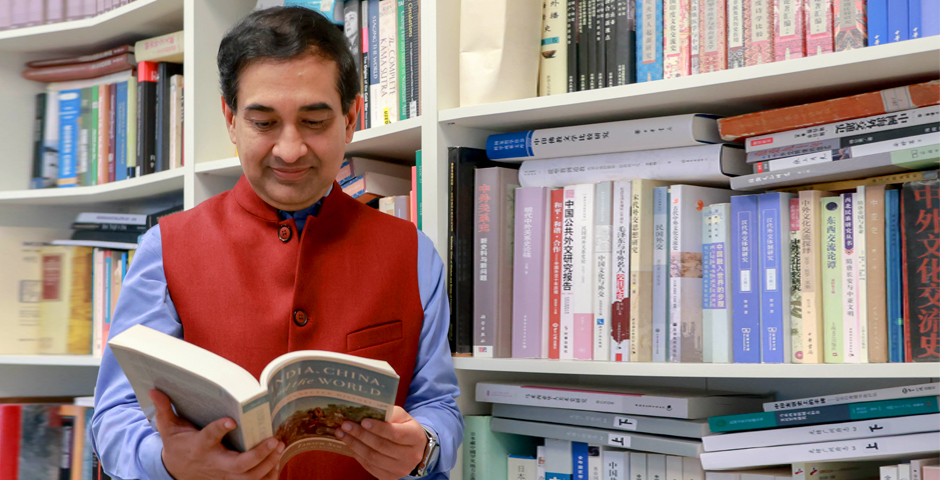

After earning a PhD at the University of Pennsylvania and teaching at the City University of New York for 20 years, Sen returned to China in 2016 to lead NYU Shanghai’s Center for Global Asia and to continue his own research into Asian history and religions, particularly in India-China interactions, Indian Ocean connections, and Buddhism.

“China and India are the two most populous countries and growing economies that have global geopolitical ambitions. As such, all these phases of India-China connections, ancient and contemporary, are crucial for understanding Asian and global histories, as well as the dynamics of contemporary politics and globalization,” Sen says.

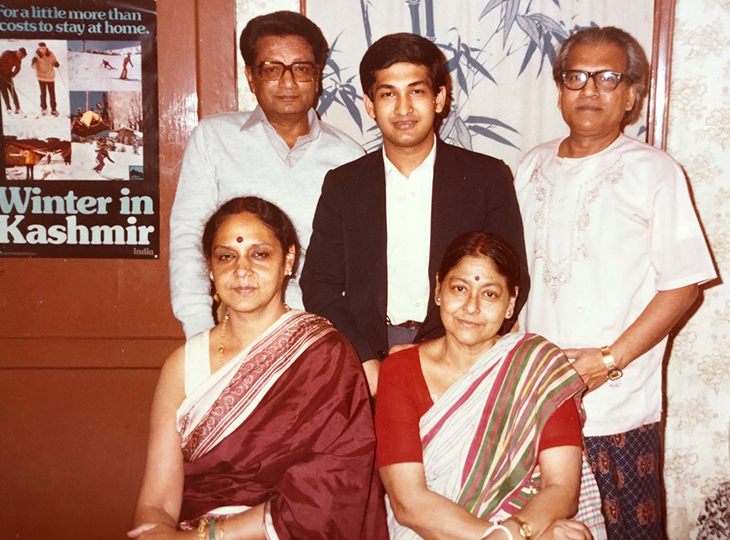

In many ways, Sen was born to build a career between China and India. His father, Narayan Chandra Sen was among the first group of Indian exchange students to China in the 1950s, studying Chinese language and literature at Peking University, and launching a prolific and pioneering career as an author and translator of Chinese books into Indian languages. The elder Sen took part in 1963’s “Friendship March” from Delhi to Beijing to promote peace between India and China, after a war took place between the two countries in 1962.

Tansen Sen (middle) with his parents (right) at their home in Beijing in 1987.

“My father was my archive,” Sen said. “We talked very frequently. He knew a lot of things I didn’t know about. I would go back and ask him about things I found in my research. If I had not come to China, I would perhaps not have studied China. I got into the field of China studies because of him.”

In addition to leading the Center, Sen today teaches three undergraduate courses - Chinese Maritime History, Concept of China, and the capstone course in Global China Studies. Sen says he designed the Concept of China course to challenge students to think more critically about seemingly basic questions, such as Where does the term “China” come from? Why is this country called “China?” and Who is “Chinese?” “Talking and exchanging views more often with students is quite interesting. I enjoy teaching courses to both our Chinese and foreign students. And it has been a good experience so far,” he says.

Sen, too, has learned from his students. Using materials from local archives including Shanghai Library and the Shanghai Municipal Archive, Sen’s capstone students have completed theses on diverse topics ranging from the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders to the Belt and Road Initiative, from plastic surgery in China to the Hanfu movement.

Tansen Sen (middle) with his undergraduate classmates and teachers in Shaoxing in 1986.

Beyond teaching, Sen is about to publish a fourth book, Beyond Pan-Asianism: Connecting China and India, 1840s-1960s (2020), a collaborative project with co-editor Brian Tsui, Associate Professor in the Department of Chinese Culture at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and 13 scholars from different parts of the world examining the complex connections between China and India, during their respective eras of imperialism and nationalist resistance. The scholars based their research on non-traditional and rarely-used sources such as the diary of an Indian soldier who fought the Boxer Rebellion during his visit to China, or the diaries of Chinese migrants in India.

“We wanted to highlight not just the political connections, but the cultural connections, literary connections, people-to-people exchange, and so forth that people usually don't focus on,” says Sen. “We learn from these exchanges that the interactions between countries are not only about politics, power, and state-to-state relations. So the main idea is to reorient the study of China and India to provide people access to archival sources and private diaries and new ways of looking at the connections between the two without focusing too much on the state-to-state relations.”

Sen is now working on several research projects, including a book on the 15th-century Chinese mariner Zheng He, a collaborative study of China-India relations during the 1950s, and co-editing the Cambridge History of the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, Sen has teamed up with Professor David Ludden at NYU and Mark Swislocki at NYU Abu Dhabi to work on “Port Cities Environments in Global Asia,” a project to connect the three campuses of NYU through a common research agenda and curricular offerings related to Asia. The project is funded by the Henry Luce Foundation. With Professor Swislocki, Sen is also planning to create a Global Network University minor in Global China Studies, with the Concept of China course taught in Abu Dhabi and in New York. “I’m excited to see where the next 40 years takes me -- and NYU Shanghai!” Sen says.