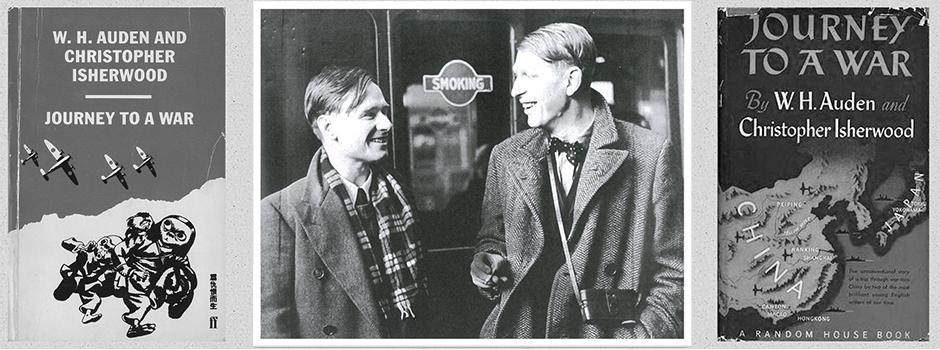

Through a reading of sonnets and prose on February 14, Professor Stephen Harder offered a unique glimpse of China in chaos and despair, witnessed by two celebrated British literary figures -- poet W.H. Auden and writer Christopher Isherwood in 1938.

Auden and Isherwood, lifetime friends and part time lovers, travelled extensively in China at the outset of the war against the Japanese invasion, including a sojourn in Shanghai. The narrative of their travels was published a year later in a rich collection of poetry and reportage, Journey to a War.

Professor Harder, a lifelong student of Auden's life and writing, said China first appeared in Auden’s poetry in as early as 1935 -- a time when Nazism and tensions in Europe were on the rise -- it became a recurring motif in his writing ever since.

Before adventuring to China, Auden witnessed the bloodshed of the Spanish Civil War in 1937 and published the poem Spain. In the concluding stanza, he buried his views on history and war:

We are left alone with our day, and the time is short and

History to the defeated

May say Alas but cannot help or pardon.

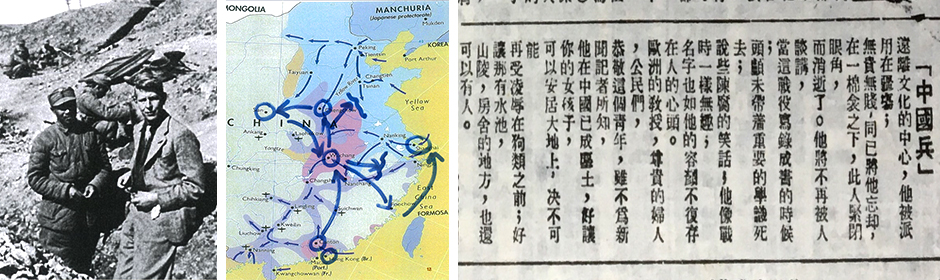

Auden and Isherwood embarked on their journey to China in January 1938. From February on, they moved from Guangzhou in South China to a string of Central China cities including Wuhan, Zhengzhou, Xuzhou, Xi’an, as well as paying visits to the Yellow River’s northwest front and the southwest Front of Jiangxi Province. Their journey concluded in Shanghai in June before a cross-Pacific voyage that led them to New York.

“Auden is the Picasso of modern poetry. He knew all kinds of poetic forms and decided to write a series of sonnets about his travels in China,” said Professor Harder. Auden wrote 26 sonnets that he called In Time of War, of which the first 12 read as completely universal in terms of language.

“He tried to explain his own mind, how history collapses into war, and how war brings terror to mankind,” Professor Harder said.

According to Harder, Auden believed that history is not something that can be “ridden forward,” but rather a tragic and sorrowful record of “human unsuccess.”

“However, literature is the news that stays the news. I believe Auden’s efforts in the 1930s are still vivid and fresh even today,” he added.

Professor Harder suggested reading Auden’s sonnet Chinese Soldier, translated and published by the Chinese newspaper Ta Kong Pao in April 1938.

Far from the heart of culture he was used:

Abandoned by his general and his lice,

Under a padded quilt he closed his eyes

And vanished. He will not be introduced

When this campaign is tidied into books:

No vital knowledge perished in his skull;

His jokes were stale; like wartime, he was dull;

His name is lost forever like his looks.

Professors of Europe, hostess, citizen,

Respect this boy. Unknown to your reporters

He turned to dust in China that our daughters

Be fit to love the earth, and not again

Disgraced before the dogs; that, where are waters,

Mountains and houses, may also be men.