Inspired by a course in Global Modernism she took in her freshman year, Haitian Ma ‘20 spent her summer intensively studying philosophy, literature and farming in a self-governing community in rural North Carolina, USA. Despite the prospect of eight weeks living in isolation without the trappings of modern life--including her mobile phone--the rising sophomore from Suzhou, China embraced the challenge and joined seventeen fellows on the selective Arete Project--a unique academic and leadership fellowship program for women. She shares with the Gazette how her summer harvesting kale, milking cows and discussing Simone de Beauvoir helped open her mind to new ideas.

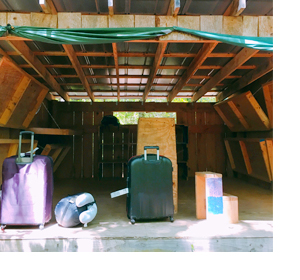

When I first arrived in the Appalachian-style shelters of Arthur Morgan School, North Carolina, I was shocked: no doors or windows, spider webs claiming residence on our wooden bunk beds. Everything was dusty, muddy, and crude. The mid-afternoon thunderstorm washed up the smell of humidity, as rain fell heavily on the tin roofs of the shelters. I lay in my sleeping bag, uncertain. How would this experience living with eighteen women in a rural academic community turn out?

Building community

The idea of community was one of the central themes we wrestled with during our eight weeks at Arete. One of the spaces where we explored it directly was the self-governance meeting where we discussed the nature of our group—our problems and potential.

This year, Arete had the most diverse student body since its foundation in 2014, and a large portion of community-building centered on cultural dynamics within the group. We wanted diversity to be an opportunity to learn from each other. But at the same time, we didn’t want cultural diversity to restrict our conversations.

As one cohort member put it during a meeting: “We did not come here for summer camp; we are here to challenge ourselves and challenge each other.”

Of course these conversations carried on outside our meetings. I found myself talking about what we wanted from our academic seminars as we harvested kale and chard for the kitchen crew to make lunch, and discussing ways for the group to reach a common understanding as we made leftover squash into experimental whole-bean chocolate muffins. Everything naturally filtered into our three-hour labor projects, which we took part in every morning from Monday to Friday.

Learning through labor

It felt great to keep the mind and body fully occupied, and sometimes the physical work gave way to sudden inspiration, like flames of light illuminating what we were navigating in our minds.

Working with our hands was not merely a romanticization of the experience away from the urban life we are used to. We did labor so that we could eat what we harvested, live in what we built, and walk on the paths we maintained; but we also acknowledged a joy beyond the practical. We became increasingly aware of the shape and texture of vegetables and fruits, the curve of wood, the flies on the skin and tail of Nettle, our cow—an attentiveness to lives as their own, not as an experience that we consume and seek amusement from.

For me, this played out in the transformation of my concept of cleanliness and dirtiness. Mud was dirty. Muck was dirtier, I used to think. Lidia Yuknavitch’s dystopian novel Book of Joan made me think differently about these oppositions of vocabulary that we use to define things. Borders blur once we live with the object closely, attentively and lovingly.

Contemplation

I couldn’t have acknowledged this and other realizations consciously without the academic leadership of our program director Laura, our passionate professor Jennifer, Tal and Kavita and my seventeen intelligent and thoughtful friends.

We wrestled with philosophical texts, such as Chinese classic Tao Te Ching; and we asked big questions--not analyzing them from a distance, but diving in with personal experiences and raw emotional reactions.

During a discussion of Beloved by Toni Morrison, everyone talked about how the novel evoked a sense of extreme heaviness in them, but I only felt tears of frustration welling up at my inability to fully understand the narrative. The support the class showed me in that moment brought us closer together and helped our conversations go deeper.

In this sense, our classes at Arete were personal: personal because we connected the questions we posed with everyday experiences that we were going through. Thanks to the possibility of vulnerability, we were able to see ourselves—and others—more clearly in the texts that spoke to us.

When reading The Second Sex by the French existentialist Simone de Beauvoir, we shared stories about self-internalized female destinies, sexual taboos and expectations that we intended to break away from.

Learning took place in all dimensions of our daily life in North Carolina; During those eight weeks at Arete, we not only lived together, we shared fears and challenges as well as friendship and inspiration. It was an experience of mindfulness, commitment and compassion—a community that depended on the support we gave to each other day to day, and one I am proud to have been part of.

---

For information and advice on applying for external scholarships and fellowships during or after your time at NYU Shanghai, contact Anna Kendrick, Director of Global Awards at NYU Shanghai: shanghai.global.awards@nyu.edu

NYU Shanghai students can also access tips and opportunity updates on the Global Awards blog.