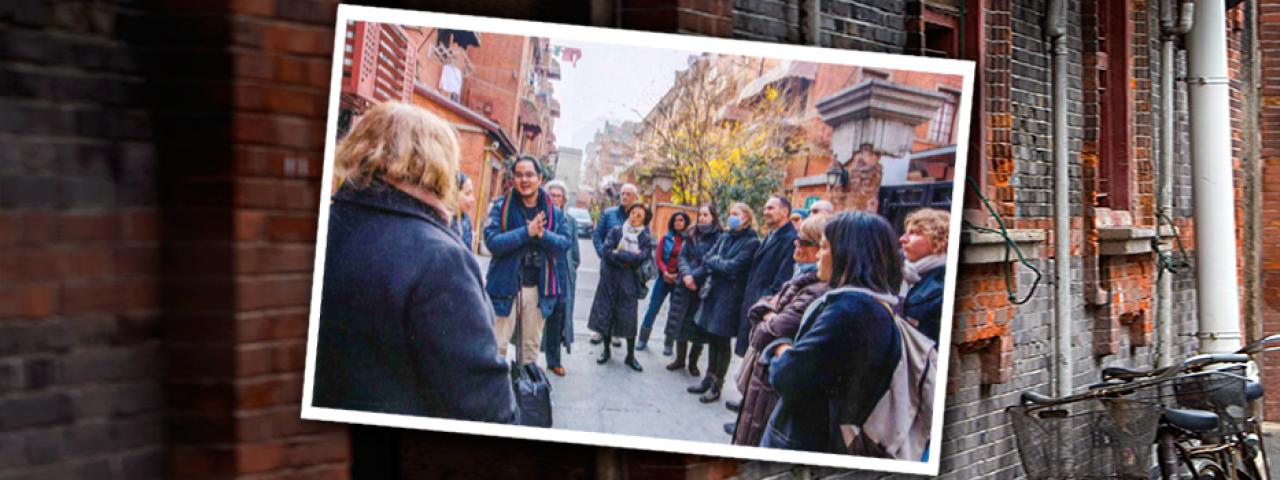

Global Perspectives on Society Teaching Fellow Non Arkaraprasertkul was recently published in Macau’s Revista de Cultura (Journal of Culture) with his article “The Death and Life of Shanghai's Alleyway Houses: Re-thinking Community and Historic Preservation. ” The following exchange reflects related insights and personal experience having lived in a lilong, or alleyway house.

What is the most rewarding thing about living in a lilong?

Every Shanghainese who lived in Shanghai before the economic reform and opening up era of the 1980s-90s have memories of the lilong — a typology of western-styled low-rise rowhouses first built by the foreigners in the concession areas during the Treaty Port period (1842 - 1942). Houses built in this particular typology would become homes to most Shanghainese for decades. These lilong houses were once everywhere in the former concessions areas. Since then, more than two thirds of them have been demolished to make way for a very different building typology -- the high-rise.

The most rewarding thing about living in a lilong is the sense of community unique to Shanghai. I had been coming to Shanghai every year since 2006, but only really learned about the lives of its people after becoming a long-term resident in the summer of 2013. Living in a lilong allowed me to discover Shanghai beyond the idealized and grandiose “postcard images” of Pudong high-rises or the historic waterfront of Puxi.

Will all of these neighborhoods eventually be replaced by high-rises?

Luckily, bulldozing lilong to replace them with high-rises will only be possible in some areas. However, like human beings, buildings do age. Many lilong have suffered a great deal from a lack of maintenance and intensive use over a long period of time, to the point of becoming unhealthy places. For these, it is better to thank them for their contribution and say farewell and make space for buildings that better suit the lives of today’s residents. When I was living in my lilong, I had an ear infection twice, alongside chronic respiratory problems because of rainwater leaks through wide cracks on the walls and the wooden floor where dust easily collected -- cleaning them thoroughly seemed an impossible task.

What is the case for preserving any lilong that have seen better days?

The local government has a vested interest in preservation to keep their level of intervention with residents’ lives to a minimum. In fact, some preservation efforts may seem rather superficial, but still better than nothing for two reasons: First, it’s doubtful that Shanghai needs more high-rises. There are many lowly-occupied, if not empty, buildings in the city that could be put to good use. Second, these low-rise lilong buildings add architectural diversity and medium density to the urban landscape. Now that some of them will not be bulldozed, we should come up with a set of policies to make them sustainable for the long term.

What can you tell us about the cramped, shared living situations that have to accommodate the lives of several families in these neighborhoods?

These spaces were by no means convenient or desirable, especially when they’re shared by 3 families of 6 residents. I often walked to the public toilet in a mall across the street because there was always someone using the bathroom when I needed to use it. The corridor was also small, so was the staircase -- from time to time I’d worry what would happen in case of fire, since the interior of the building was made of wood.

Are shared spaces (like kitchens and bathrooms) typically inconvenient necessities?

At first I didn’t think that these shared spaces had anything to do with the community bond, until one morning my neighbors and I happened to be cooking together in the corridor where both of our gas stoves were located. (I didn’t usually have time for breakfast, often buying a piece of bread from a nearby bakery -- but that day I was in the mood for a stove-top espresso and soup). In the cramped, shared kitchen, there wasn’t anything else to do but to stand. It was too small to fit a chair, so both my old neighbors and I stood together, waiting for our food to be cooked. What else could one do in that situation if not strike up a conversation?

Located right by the staircase, the kitchen would welcome any neighbors walking up or downstairs. Whenever two people started talking, the congenial sound of conversation often attracted nearby neighbors to join in. Some were just curious about what we were saying, some were lonely or didn’t have anything else to do, and some just wanted to be seen. Over time, we’d learned more about each other, and became more trusting of and helpful to each other.

How does the internationalization of Shanghai impact the sense of belonging in these communities?

In interesting ways! On the bright side, new residents, such as the 20 foreigners and more than 50 young entrepreneurs living there with me, bring much desired diversity, as well as income, to locals, contrary to what many may think. For many old residents, newcomers bring contemporary forms of livelihood. Some become friends with their older neighbors, helping children in the community learn English, for example. With the decline of the “iron rice bowl” safety net, older locals also benefit from much-needed extra income by renting out their spaces. My landlord, for instance, always booked an appointment with his doctor on the Thursday of the first week of the month — right after he came to collect my rent, which he needed to pay for his medical bills.

The young gentries -- to use a political economy term -- also made the old locals more aware of the time and place in which Shanghai is in. Many shared with me that they felt as though they had to make a conscious effort to change personal behaviors -- spitting on the street, using loud voices, and not keeping the front of their houses clean--so as not to embarrass themselves in front of their new neighbors.

There were of course, negative impacts, such as the decline of trust among neighbors. With a more diverse community, there were more strangers and passers-by in the neighborhood. Some of these strangers did not understand the local lifestyle and disturbed the peace by drinking ferociously at night and being too noisy, preventing the locals (mostly retirees) from sleeping. Also, some neighbors might be financially better off than others because they were able to rent out their places at a higher price. Those who did not enjoy the same benefits were often jealous. Making matters worse, some tenants become landlords themselves, thereby deceiving the old residents and subletting their spaces for large sums and pocketing the difference.

Can regentrification be made to work in lilongs?

In my research, I have come up with the concept of “gentrification from within” to explain the phenomenon whereby lilong communities have become more diversified thanks to the recognition from the international community for being "culturally and historically significant,as well as located centrally.” Yet unlike in most places where gentrification has had a rather negative impact by depriving the underprivileged of their homes, the process of "gentrification from within" so far has made the community more diverse (as more new residents are moving into the lilong), more financially sustainable (by way of the original residents renting their extra spaces to outsiders), and more livable (as people from different age group, class, educational and socioeconomic background are living together and learning from each other). It is still too early to say whether this process would be considered viable in the long run because it relies solely on the effort of individuals who are trying to make the best out of the situation in which they find themselves. Local policymakers need to understand this dynamic and the benefits of involving ordinary residents in the process of sustainable social change.