A group of NYU Shanghai and NYU scientists has uncovered how heavy, motorized objects climb steep slopes—a newly discovered mechanism that also mimics how rock climbers navigate inclines. The findings, which were recently published in the international interdisciplinary journal Soft Matter, stem from a series of experiments in which motorized objects were placed in liquid and then moved up tilted surfaces.

NYU Shanghai Professor of Physics and Mathematics Jun Zhang participated in the project and concluded the research. Other main co-authors included Postdoctoral Researcher at the Courant Institute at the time of the research Quentin Brosseau, Doctoral Candidate in NYU’s Department of Chemistry Yang Wu, Professor in NYU’s Department of Chemistry Michael Ward, NYU Associate Professor of Mathematics Leif Ristroph, and Professor at the Courant Institute Michael Shelley.

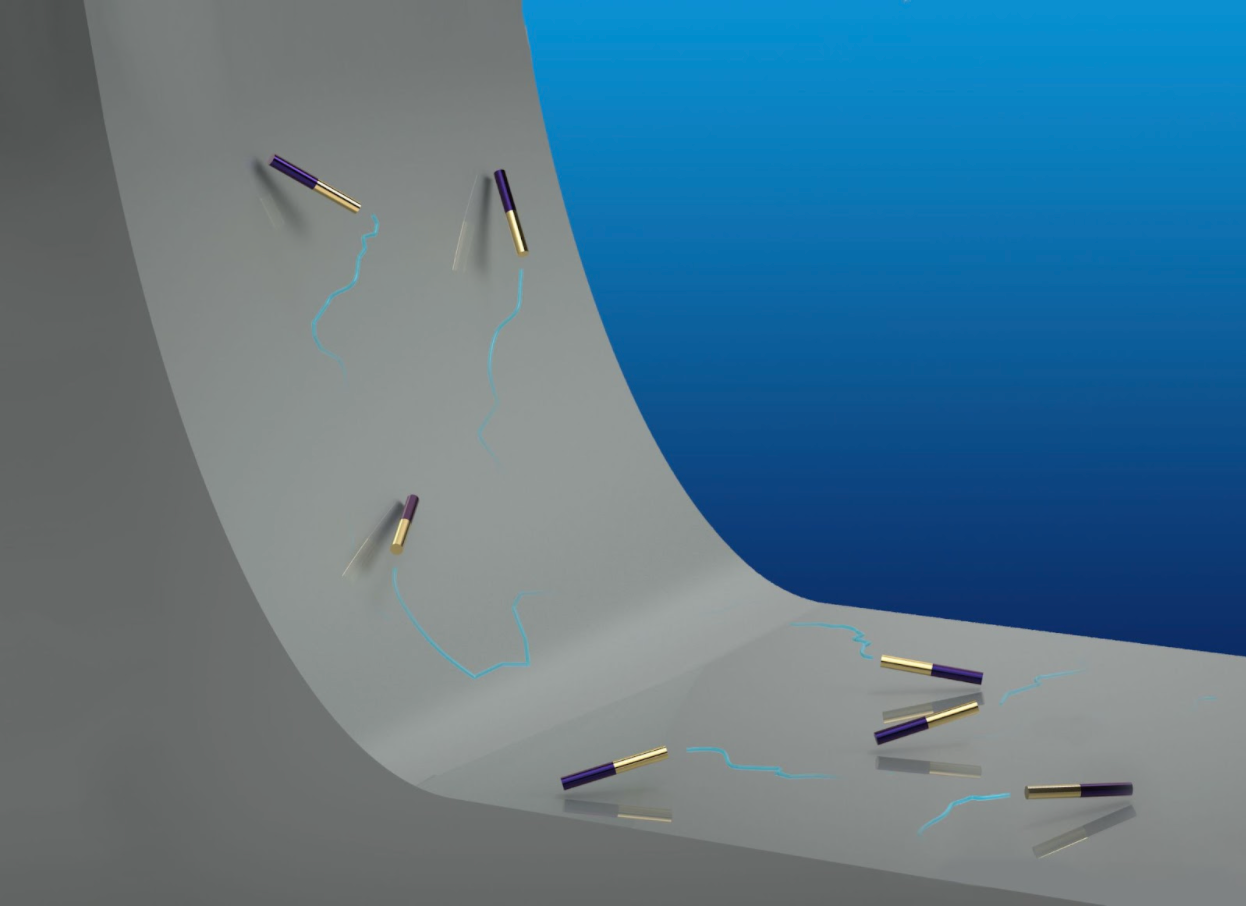

In the Soft Matter research, scientists created swimmers, or nanorods, whose length is roughly 1/40th the width of a strand of human hair. These motorized swimmers were tasked with moving up an inclined surface while immersed in a liquid solution within a walled container. The swimmers were composed of two types of metal—gold and rhodium as well as gold and platinum—a makeup that gave them unbalanced densities given the varying weights of these metals.

“These ‘micro-swimmers’ are about 20 times heavier than the fluid they swim in, but they were able to climb steep slopes that are almost vertical,” explains Jun Zhang. The swimmers’ composition, liquid environment, and juxtaposition of surfaces enabled them to move upward, despite their significant weight.

Heavy metallic microswimmers, made of rhodium (purple) and gold, swim around in a liquid solution. When confronting a sloped wall, each rod-like swimmer will reorient its body upward due to its density imbalance, and swims up like a rock climber against gravity. A hydrodynamic effect helps to amplify the action in its reorientation.

The work enhances our understanding of “gravitaxis”—directional movement in response to gravity. The phenomenon is a vital consideration in not only engineering, fluid mechanical control in the microcosmic world, but also in medicine and pharmaceutical development. It explains, in part, how bacteria move through the body and provides insights into ways to create more effective drug-delivery mechanisms.

“These motors reorient themselves upward against gravity thanks to their density imbalance—much like a seesaw reorients itself in response to the movement and weight of its riders,” adds Michael Shelley. “A hydrodynamic effect amplifies this movement—swimming next to a wall yields a bigger torque in repositioning the motors’ bodies upwards. This is important because the microscopic world is noisy—for the motor it’s always two steps up and one step down—and the bigger torque improves their ability to move vertically.”

In previous work, published in Physical Review Letters, Zhang, Shelley, and their colleagues created “nano-motors” in uncovering an effective means of movement against currents. The new research expands on these findings by revealing how heavy objects can move up steeply inclined surfaces, offering the promise of even more sophisticated maneuvers.

“Now that these micro-swimmers are able to climb very steep slopes against gravity, we can look toward developing even more difficult assignments,” observes Zhang. “Future, advanced motors will be designed to reach targeted locations and to perform designated functions.”

----------

Original Article by James Devitt, NYU Public Affairs