When it comes to conflicts that shaped the history of modern China, the Second World War often gets all the attention. But World War I - also known as the Great War - played an important role in forming the revolutionary currents and international relationships that set modern China’s course, according to original research by Xu Guoqi, Kerry Group Professor of Globalization History at the University of Hong Kong.

In a March 9 talk hosted by NYU Shanghai, “China and the Great War,” Xu took over 70 participants inside the lives of 140,000 Chinese laborers on the frontlines of the Great War. The talk was presented by the NYU Shanghai-East China Normal University Center on Global History, Economy and Culture (CGHEC), with an introduction and discussion moderation by CGHEC co-director and NYU Shanghai Distinguished Global Network Professor Chen Jian.

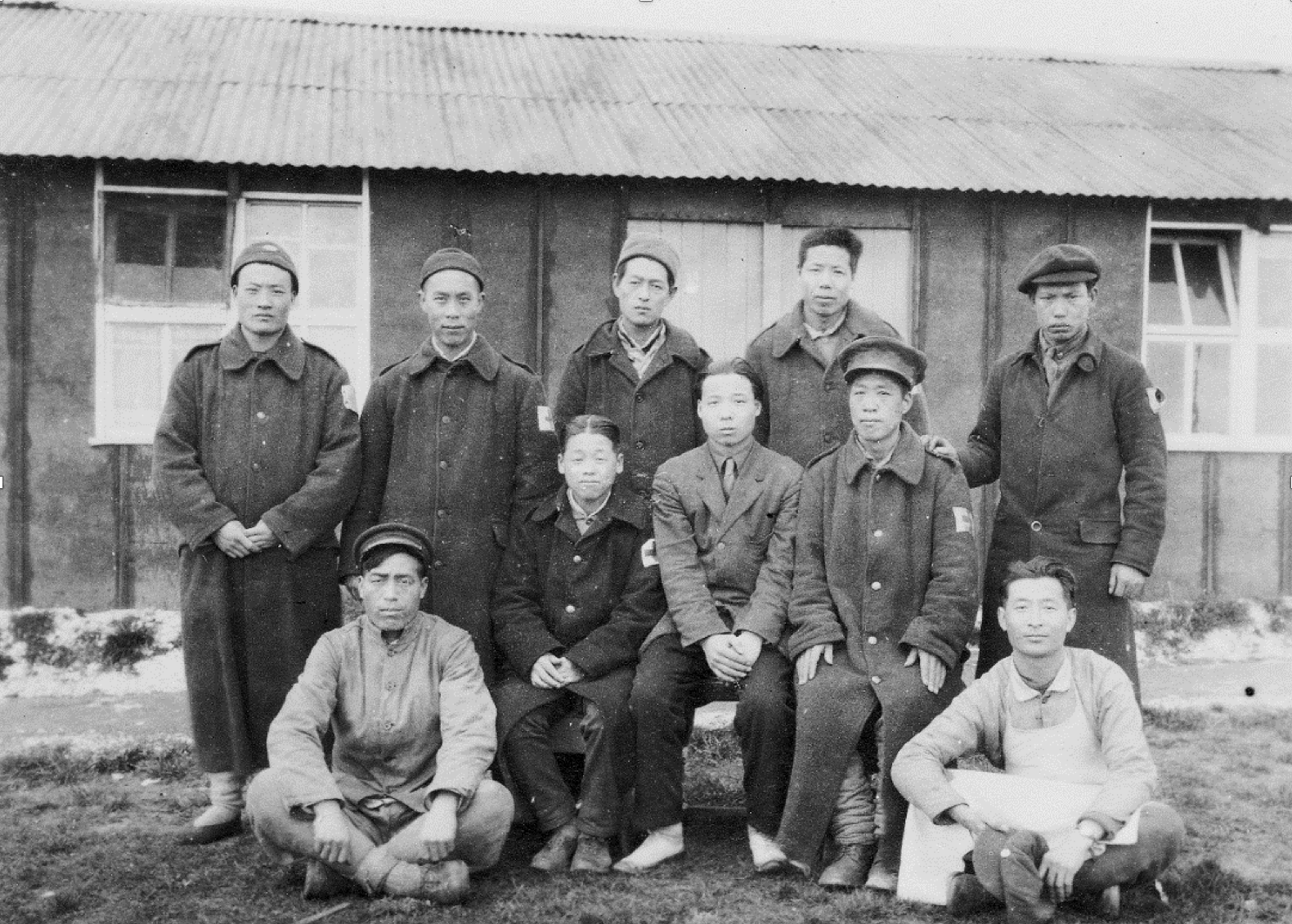

Kitchen staff and staff of a Chinese hospital in France. Photo: Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota.

The 1910s were a tumultuous decade for the whole world. As war loomed over Europe, China abolished its monarchy, became a republic, and faced enormous threats from Japan and other imperialist countries. According to Xu, the Great War presented both immense danger and opportunity to China. “The Great War is the beginning of the story, a turning point for China’s internationalization,” Xu said.

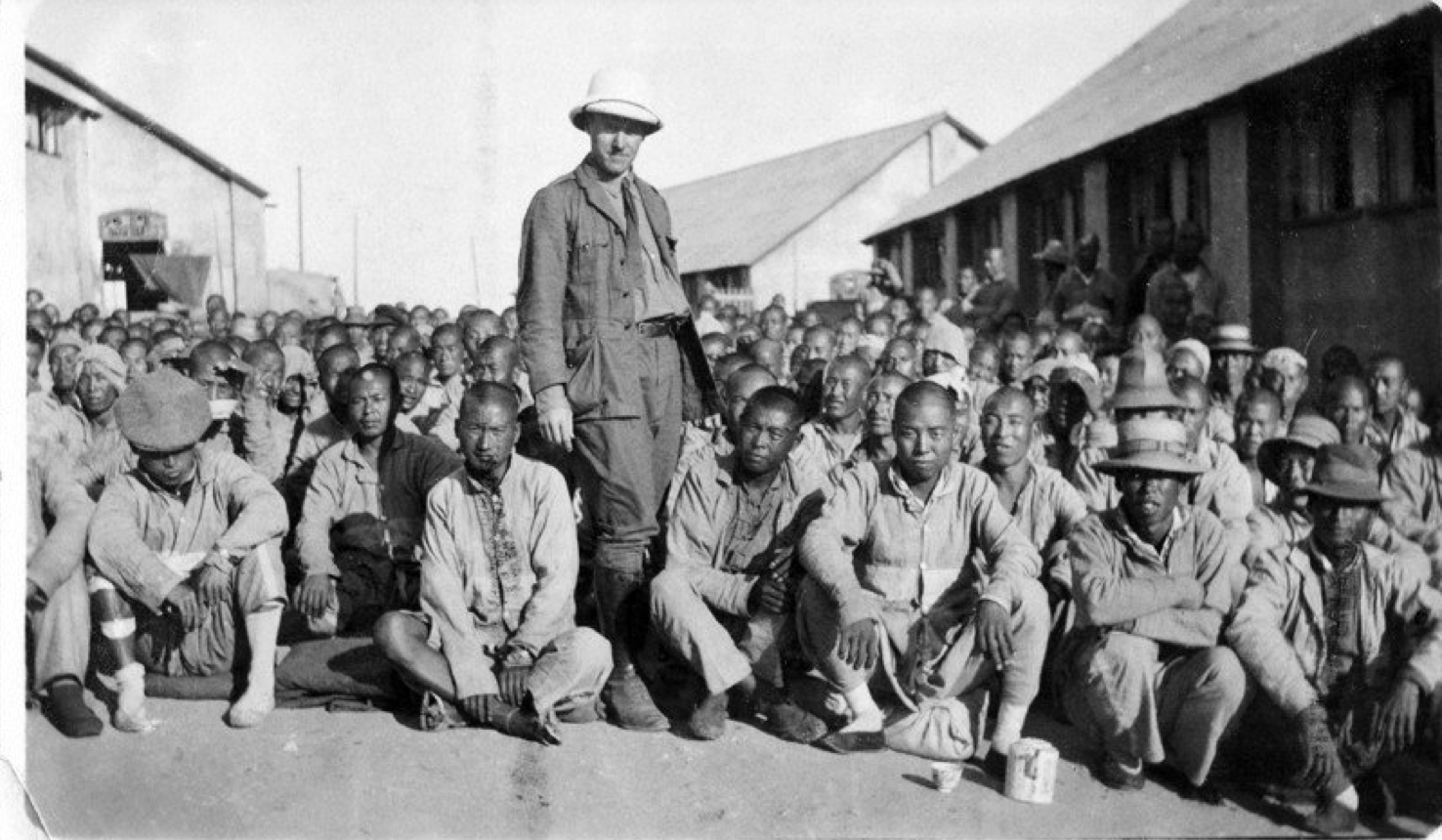

Xu’s talk focused on a group of important but largely forgotten people, the “workers in the place of soldiers” who formed the Chinese Labor Corps, laborers specially selected by the Entente Powers (Britain, France, and their allies) and dispatched to the Great War’s western frontline by the Republic of China. Sending laborers to Europe was China’s only way to contribute to the Entente and earn a seat at the post-war negotiation table, Xu contended.

Chinese Labor Corps workers washing a Mark V tank at the Tank Corps Central Workshops, Erin, France, February 1918. Photo: Imperial War Museums.

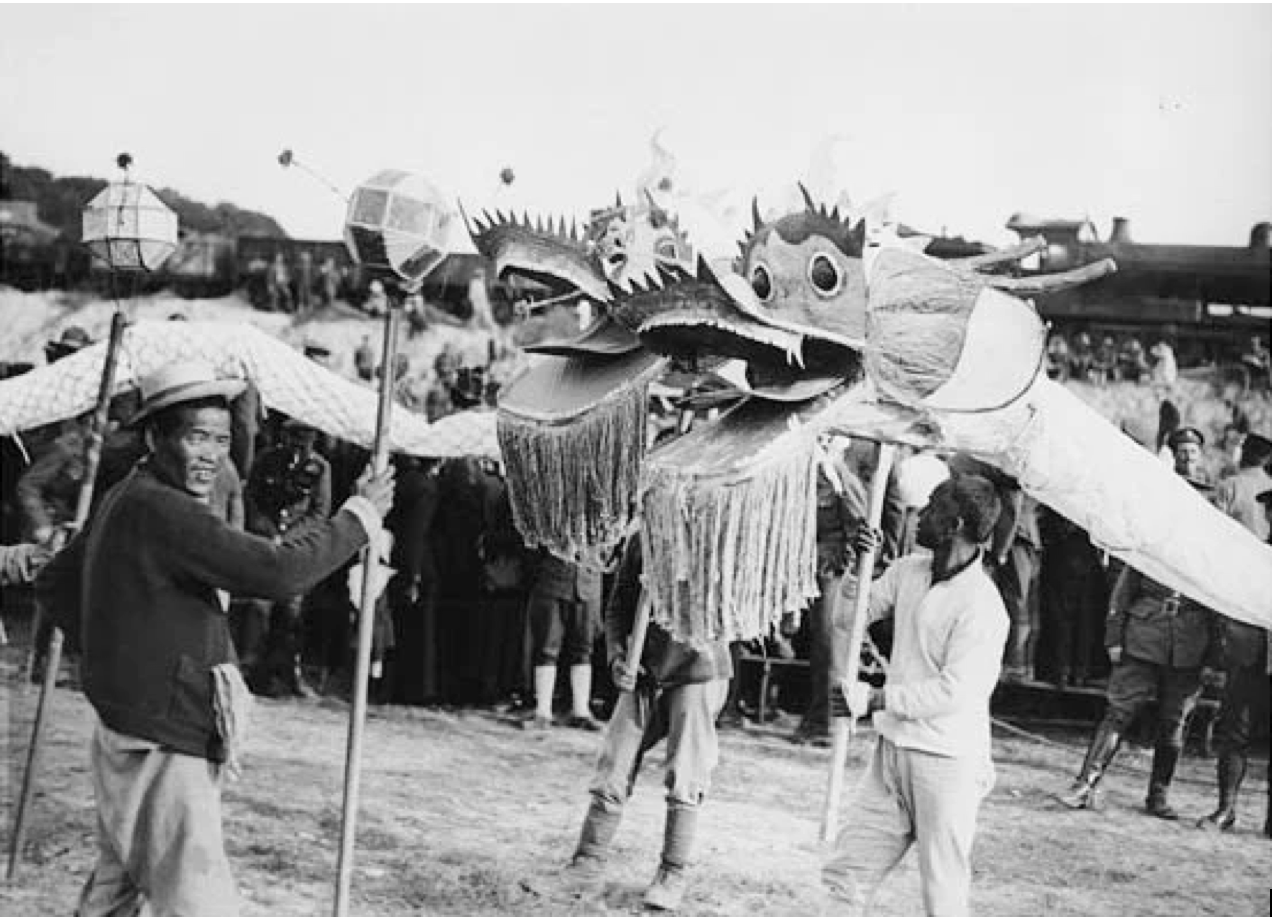

Many of the roughly 140,000 workers of the Labor Corps might never have ventured more than 10 miles from their villages before boldly traveling halfway around the world into the jaws of war, Xu explained. But when they arrived in Europe, Labor Corps members played an important role on the Western front, digging trenches, repairing tanks, assembling shells, and assisting the Entente forces wherever labor was needed, regularly interacting with European servicemen and local populations.

“Every ordinary person, at a certain time, could play a very important role in shaping history,” Xu contended. Even though most members of the Chinese Labor Corps were illiterate farmers, Xu argues that they played a crucial role not only in winning the war for the Entente, but in shaping China’s role in the new world order that emerged as empires fractured into nation-states worldwide. The Labor Corps members’ contribution to the war gave China a claim to join the international community as a nation with equal status.

Chinese laborers performing a Dragon Dance in their living quarters near a train depot in France. Photo: National Library of Scotland.

But Xu noted that the direct outcome of the Versailles peace negotiations that ended the Great War disillusioned China with the West. Despite China’s contributions to the Entente’s efforts, instead of returning sovereign authority over German concessions in Shandong to China, the Treaty of Versailles acceded the concessions’ transfer to Japan. As highly as Chinese people thought of Woodrow Wilson before the Treaty, Xu said, so deep was their disappointment in Wilson and his principles afterwards. “The result of World War I and the Treaty were directly connected with the founding of the Chinese Communist Party and the May 4th movement,” said Xu. “It was the cornerstone of China’s communist revolution.”

Workers gather for selection to the Chinese Labor Corps in Weihai. Photo: Weihai Archives.

More than a century has passed since the Great War ended. Today, the graves of the Chinese laborers who sacrificed their lives in the Great War still stand peacefully in French and Belgian veterans’ cemeteries, as a testament to how China helped Europe survive one of its darkest hours, and as a reminder of the role these laborers’ sacrifice played in helping China find its way through its own period of darkness. Chen summed up Xu’s talk with a call to remember the sacrifices of these both ordinary and extraordinary men. “In both world wars, China stood on the right side of history. We must be very, very thankful for our predecessors, for all the sacrifices and efforts they had made, which made a difference in Chinese history, which made a difference in world history,” Chen said.

Chinese laborer and Belgian boy, Belgium, 1917. Photo: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres.

Special thanks to Wang Yiling, Associate at the NYU Shanghai-East China Normal University Center on Global History, Economy and Culture, for drafting this report.