Perhaps no city has grown and urbanized, and transformed itself into a modern metropolis as rapidly as Shanghai.

The city’s iconic skyline—the spaceship-like Pearl Tower, the gleaming World Financial Center, the elliptical Shanghai Tower, all standing tall amidst a gleaming glass forest of skyscrapers along the Huangpu River—has become an indelible symbol of China.

For many, it’s difficult to believe that just over 25 years ago, the busy Pudong District was home to scattered warehouses, wharves, and mud flats. Or that a little over 100 years ago, Yan’an Road, now one of modern Shanghai’s major thoroughfares, was a stream along whose banks farmers sold watermelons and other produce.

Or that some 600 years ago, Shanghai—Zaanheh, as it has long been called by its residents in the local dialect—was a water town, where boating along canals was the most common form of transportation.

In the daily, urgent hustle of 21st century city life, it is easy to forget the past. And yet hints of the past are still with us—even in futuristic Shanghai: Major roads such as Zhaojiabang Road and Lujiabang Road are named for the waterways they replaced. Small pockets of wetlands and tall grasses can still be found in the city’s outer districts. Shanghai’s soft, sandy soil and tropical summers—these are not only the legacy of Shanghai’s water-saturated past, but also its present. And, with climate change already making its presence felt every day, its likely future.

“WHAT IF YOU COULD WALK AMONG THE RHINOS AND GIBBONS

THAT MIGHT HAVE ROAMED SHANGHAI 7,000 YEARS AGO?”

What if Shanghai’s residents could travel back in time and experience some of those past landscapes? What if anyone could type in a current Shanghai address into a computer, don a pair of virtual reality glasses and walk among the rhinos and gibbons that might have lived on that particular street 7,000 years ago or board a boat to explore the 15th century canal that ran past their front door? Or put on a pair of headphones and listen to the insects, cranes and other birds that populated Shanghai’s wetlands so many centuries ago?

Through the Zaanheh Project, a multi-disciplinary team of NYU Shanghai professors and staff, graduate and undergraduate students are attempting to research and create a comprehensive history of Shanghai’s landscape and ecology. By using all the materials and tools available to us today—historical, geological, ecological records, maps, paintings, poems, data science and computer modeling—team members hope to create a complete understanding and experience of Shanghai’s natural landscape, ecology and geography at distinct points in time.

Zaanheh is directly inspired by the Mannahatta Project, a decade-long study undertaken by Eric Sanderson, a conservation ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and an adjunct lecturer in NYU’s Department of Environmental Studies. Mannahatta suggests and interprets what the island of Manhattan might have looked like in the moments before the English explorer Henry Hudson and his crew landed there in September 1609. With computer modeling, maps, historical and archeological records, Sanderson and his colleagues recreated in a book and online “the forests of Times Square, the meadows of Harlem, and the wetlands of downtown” that were home to Native Americans who lived among mountain lions, elk, deer, beavers, tens of thousands of bird and fish species in the early 17th century.

Manhattan in 1609 and 2009: The Zaanheh Project was inspired by Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta Project, which traced the ecology of New York City to before the arrival of colonial settlers. Credit: Markley Boyer / Wildlife Conservation Society; Yann Arthus-Bertrand / Corbis.

The idea to undertake a similar project in Shanghai happened serendipitously. In 2017, Sanderson came to China to give a talk about the Mannahatta Project at the Shanghai Zoo. At NYU Professor Dale Jamieson’s suggestion, Sanderson stopped by the NYU Shanghai campus to visit Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Li Yifei. As they talked, the two had a brainstorm, “Why not do this for Shanghai, too?”

There was clearly a need for the project, says NYU Shanghai Dean of Arts and Sciences Maria Montoya, who is spearheading the effort. While it’s not too difficult to find books, articles and photos documenting the changes in Shanghai’s urban landscape over the last three decades, there has yet to be a comprehensive accounting of Shanghai’s past geography, ecology, and biodiversity. Though covering a much shorter timespan, the city’s museum of urban planning, for instance, is still larger than Shanghai’s natural history museum. And the vast majority of people—Shanghai residents included—know little of Shanghai’s ecological past beyond romantic stories of its origins as “a small fishing village.”

The idea of a Zaanheh Project that might fill in these gaps quickly captured the imagination of a large interdisciplinary team of NYU Shanghai faculty, graduate students and undergraduates from disciplines such as Interactive Media Arts, History, Philosophy, Art History, and Computer Science. Sanderson, too, signed on to be a key consultant.

Montoya says that team members are working to expand and recruit experts from Shanghai universities and around the world to the join the Project. The NYU Shanghai-ECNU Global Center for History, Economy and Culture has become the Project’s sponsor, opening doors to potential partners at regional regional and cultural organizations. The Academia Sinica in Taipei has begun sharing their extensive collection and analyses of ancient and antique maps of the Shanghai region. Berlin’s Max Planck Institute, which has digitized some 3,000 Chinese Gazetteers—encyclopedias recording the history of Chinese localities at various points in time—has also made their research tools available to the NYU Shanghai team.

“Our hope is that this project will become a lasting gift from NYU Shanghai to the city of Shanghai,” says Vice Chancellor Jeffrey Lehman. “We hope that it will help the people of Shanghai both to better appreciate their city’s rich natural heritage and to use that knowledge to better meet the inevitable ecological challenges of the future.”

While the project is still in its very nascent stages, the team for now is focusing on Shanghai’s natural landscape at three key points in time:

• Seven thousand years ago, during the Majiabang period, when elephants, rhinos and tigers roamed the wetlands.

• 5th century, in the late Jin through the Tang Dynasty, when Shanghai was still a small fishing village called Hu (滬).

• 1842, on the eve of the the Foreign Concession period after the first Opium War.

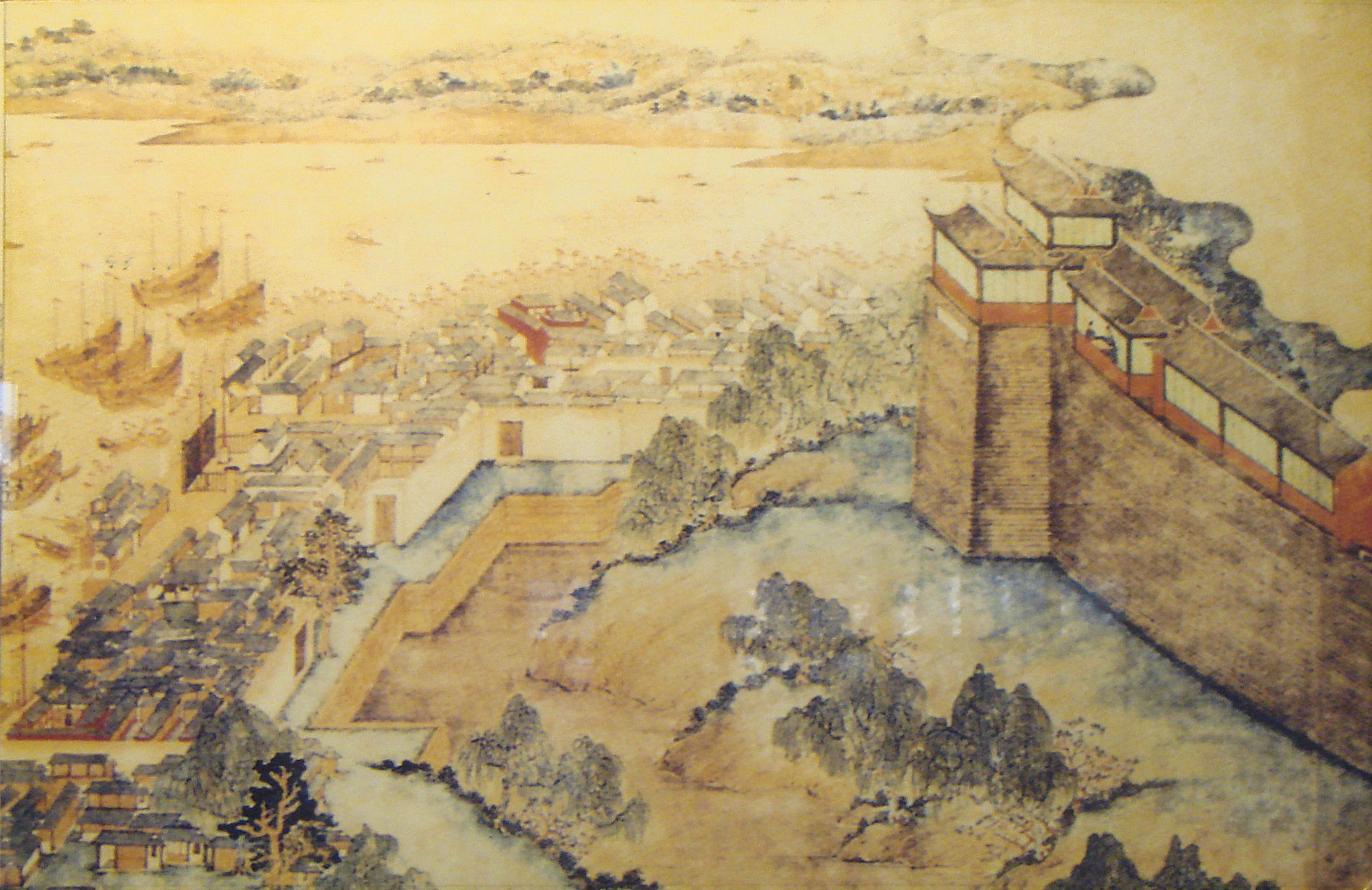

A 17th-century painting of the river port and moat outside the city walls of Old Shanghai.

The research team is looking to produce several outputs at the end of what they expect will be at least a decade-long process:

1. Articles and books to build international interest in the subject matter.

2. Interactive web-based map/virtual reality tools for public use.

3. Educational material for students in grades K-12.

4. Recommendations for better management of floods, parks, wetlands, etc, based on our understanding of the past.

5. A network of interdisciplinary scholars or research teams in Shanghai and beyond.

But before any of these outputs can be achieved, years of painstaking research lay ahead. An already robust body of scientific knowledge, from the sedimentary history of the lower Yangtze delta to the social evolution of human settlements in the region, will serve as the foundation for the team’s exploration and intellectual undertakings. The story of Shanghai’s ecological past must also be pieced together from reams of original records left behind by Zaanheh’s long ago residents, rulers, and visitors—from the thousands of gazetteers dating from 1193 that were compiled by local scholar-officials to describe Zaanheh’s geography, physical features, population, to the diaries and records of the Jesuit missionaries who traveled to China in the 16th century, to the meticulous and comprehensive handwritten minutes of the Shanghai Municipal Council formed by the British, French and Americans to oversee city affairs during the concession era, to the archives of the Shanghai waterworks.

Li says he sincerely hopes that a decade from now, he will still be fully immersed in the ongoing Zaanheh Project. Its possibilities and end products are more than worth the time. “As a Shanghai native, my hope is that everyone can better understand the city in the historical context in which it emerged,” Li says. “I’m doing nothing more than dusting off some of the richest stories of Shanghai’s past. Let them shine in a way that they so richly deserve.”