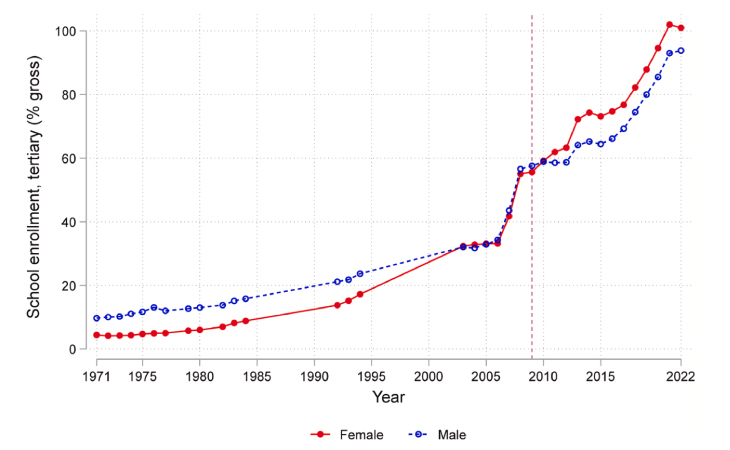

A profound shift has changed the classroom dynamic worldwide over the past several decades: women have not only caught up to men in educational achievement, but have increasingly surpassed them, reversing a long-standing gender gap in education.

To explain this “reversed gender gap,” economists tend to look at labor market incentives and psychologists often point to differences in behavioral skills or maturity levels. A new study co-authored by University of Hong Kong Associate Professor of Sociology Xu Duoduo and NYU Shanghai Yufeng Global Professor of Social Science Wu Xiaogang offers a compelling structural explanation for the phenomenon: when artificial barriers are removed, female academic advantages naturally emerge.

The study, which was published in the journal Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, leverages a unique “natural experiment” in Hong Kong to demonstrate how equal opportunity policies can trigger a reversal in gender inequality.

From Lecture Hall Observation to Empirical Evidence

Professor Wu was inspired to conduct the study after noticing gender imbalance in his classroom. “I spent a substantial part of my academic career in Hong Kong,” he recalls. “In my Social Stratification course, I consistently noticed that nearly 90 percent of the students were female. When I asked students why, they offered various explanations, from the pressure to outperform men due to labor market discrimination, to girls simply having better language skills.”

While these explanations were plausible, Wu found them too provincial. He observed a broader pattern: the reversal of the gender gap had already occurred in the West, followed by Hong Kong, and later mainland China. “This comparative perspective suggested that broader social mechanisms, rather than just cultural factors, were driving these changes,” Wu says.

He encouraged his then-student, Xu Duoduo, to investigate this trend using causal inference methods. Together, they found the perfect case study in Hong Kong’s educational history.

The “Natural Experiment”: Hong Kong’s 2002 Reform

For decades, Hong Kong’s Secondary School Places Allocation (SSPA) system employed a controversial mechanism: gender quotas. Because girls historically performed better in internal primary school assessments, the system artificially adjusted scores and set quotas to ensure a “balanced” sex ratio, effectively protecting boys from competing directly with their higher-achieving female peers.

In 2002, following a court ruling that deemed the policy discriminatory, the quota system was abolished in favor of a strictly merit-based admission process.

“Equal opportunity” is a subtle concept not easily measurable on an empirical ground. We take advantage of a reform in the school allocation system in Hong Kong to gauge the impact of implementing an equal-opportunity policy on the gender gaps in learning outcomes. This sudden policy shift provided us with a quasi-experimental design,” says Wu. “It allowed us to see exactly what happens to the gender gap in academic achievement when the ‘affirmative action’ that was secretly benefiting boys is removed.”

Unleashing Potential Through School Sorting

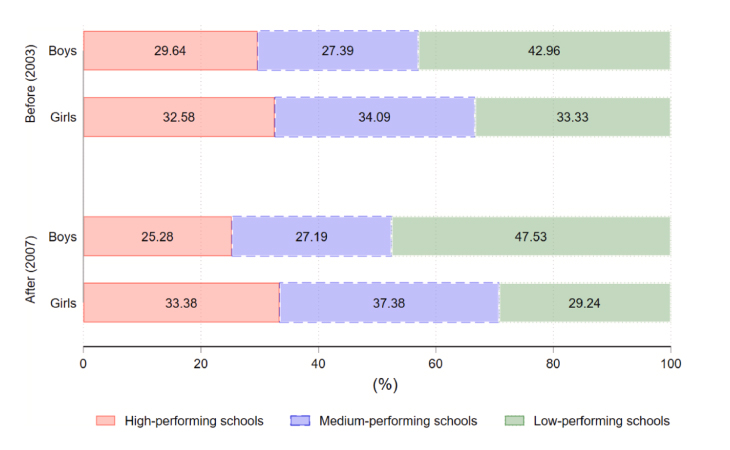

Using data from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), the researchers compared the performance in mathematics and science tests of two cohorts of students (Grade 4 and Grade 8), one affected and the other not affected by the SSPA reform. They used a “Difference-in-Differences” (DID) approach, comparing 8th graders (who were affected by the secondary school admission policy) with 4th graders (who were not).

The findings were striking. After the removal of protections for boys, the gender gap in mathematics and science didn't just close—it reversed. Girls began to significantly outperform boys.

Crucially, the study identified why this happened. It wasn't that girls suddenly changed their behavior in the classroom. Instead, the mechanism was school sorting.

“Under the merit-based system, girls secured more seats in higher-quality schools, while boys became overrepresented in lower-quality schools,” Wu explains. “Because school quality is a primary driver of academic success, this shift amplified girls’ advantages.”

Reframing Equal Opportunity

The study appears to be a local issue, but the findings have broad implications. Xu and Wu research challenges the assumption that boys naturally excel in math and science while girls are more talented in the arts. Instead, it suggests that male dominance in STEM fields may have been historically preserved by institutional structures that favored men.

“These results reveal how gender quotas had structurally constrained girls’ academic potential,” Wu explains. “They demonstrate that equal opportunity policies, which have afforded girls with an equal footing with boys in classroom learning, do not merely level the playing field—they unleash girls’ pre-existing advantages in behavioral and social skills relative to boys.”

However, the findings also point to the complexities of educational reform. “As societies strive for fairness, the implication is practical,” Wu adds. To avoid creating new imbalances, he says, “policymakers need to look beyond admissions rules and address the disparities in quality between schools themselves, and perhaps also distinctive developmental paths between boys and girls.”