The last time Yufeng Global Professor of Social Science Wu Xiaogang worked in Shanghai, the city and its Pudong skyline were still in the earliest days of its twenty-first century metamorphosis. Hired out of Peking University in 1994 to work in the Research Office of the Shanghai Municipal Government, Wu recalls visiting a more modest Lujiazui, before the World Financial Center and the Jin Mao Tower dominated the Pudong skyline: “The cleared-up sky after a storm, the muddy lane near the Dongchang Ferry, and the smell of you dunzi [a Shanghai street-food] wafting through the air” are among his most pungent memories of his first stint in Shanghai.

The intervening quarter century has been transformative for Shanghai; and for Wu himself, who left the Shanghai government in 1996 to pursue a PhD in the United States and returned last year as a leading sociologist studying post-reform China.

Over the years, Wu’s research has focused on socioeconomic change in China and its impact on Chinese society and people - from social stratification and inequality to migration and education to child development and population aging. Since arriving at NYU Shanghai from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), Wu has launched the NYU Shanghai Center for Applied and Social and Economic Research (CASER), where, expanding on his work at HKUST, he is, among other projects, leading efforts to build a comprehensive database to support comparative studies of Chinese cities, including Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Shenzhen. The goal is to work with governments and NGOs to use these findings to develop effective policies to promote people’s wellbeing. “I feel grateful that NYU Shanghai has given me a great opportunity to conduct localized research with global impact," Wu says.

Wu’s arrival on campus will undoubtedly strengthen NYU Shanghai’s efforts to make significant and meaningful contributions to its hometown, says Provost Joanna Waley-Cohen. “We wanted to recruit Wu Xiaogang for multiple reasons relating to his scholarly excellence but it comes down to this: he is a highly esteemed sociologist much of whose past and ongoing research relates specifically to the city of Shanghai,” Waley-Cohen says. “His work provides an opportunity to leverage our location to generate new data on the great city where we are located and at the same time hopefully the city will find it useful to draw on his findings to inform policy and planning.”

Journey from Shanghai and Back

When he left Shanghai for the University of California at Los Angeles, Wu says he expected to spend his career conducting comparative studies of the cities of the Asia Pacific. But he eventually found himself intrigued by the economic reform taking place in his home country, particularly their impact on social inequality and social mobility, in comparison to other former socialist countries in Eastern Europe and Russia. After earning his PhD, and serving a post-doc at the University of Michigan, Wu returned to China, taking a post at HKUST. Even then, Shanghai figured in his research.

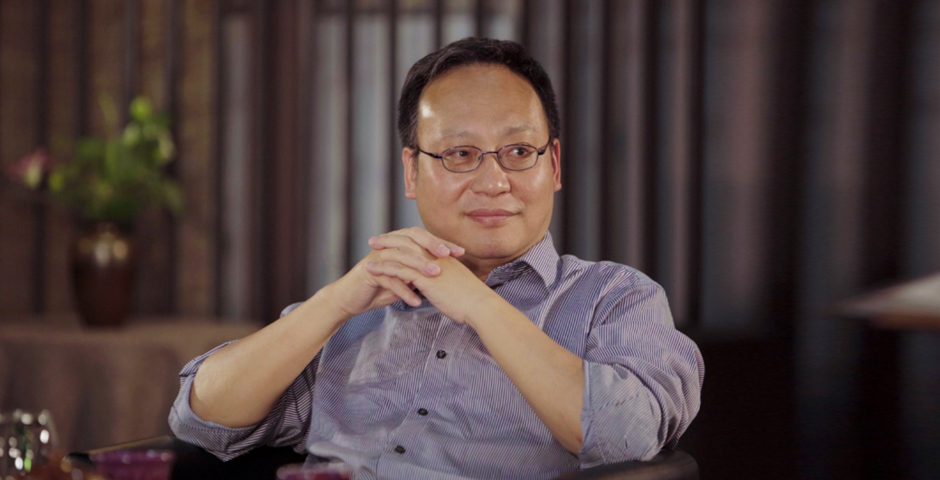

Wu in Shanghai in the 1990s

As founder of the Center for Applied Social and Economic Research (CASER) at HKUST - the predecessor to NYU Shanghai’s CASER - Wu initiated and co-directed several projects, including the Hong Kong Panel Study of Social Dynamics (HKPSSD) and the Shanghai Urban Neighborhood Survey (SUNS), a collaborative study with Shanghai University to build a comprehensive database for in-depth exploration of key issues related to urban residents’ livelihood, such as education, health, housing, inequality and poverty, migration, population aging, and urban governance. As the proportion of city dwellers in China continues to grow, exceeding 60% of the entire national population in recent years, studying the development of Chinese metropolises such as Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Shanghai, Wu argues, will be key to understanding “the future of Chinese society.” And, since China is still urbanizing, the country still has the opportunity to ensure a more people-oriented urbanization than countries that are already developed.

“Social cohesion” a rich field of urban research

Recently, Wu and his colleagues at CASER, first in Hong Kong, and now in Shanghai, have been applying the concept of “social cohesion” to understanding China’s urban neighborhood life and governance.

One might expect that urbanism would diminish the development of close social connections between neighbors. But in their Shanghai neighborhood study, Wu and his colleagues have found that not only has social cohesion survived in many neighborhoods, an inverse relationship exists between social cohesion and the socioeconomic status of residents, in contrast with previous studies on Western cities. The elderly in these neighborhoods enjoyed higher social engagement, which, along with friendly neighbor relations, significantly improved social cohesion and individuals' mental and physical health.

CASER researchers also found that social cohesion could play a valuable role in helping communities overcome challenges and difficulties during a sudden crisis. During Wuhan’s COVID-19 lockdown, NYU Shanghai Assistant Professor of Sociology Miao Jia and her team found that members of China’s unique network of neighborhood committees (juweihui) and residents working as volunteers came together to help each other both logistically and emotionally with the challenges of the long lockdown. (Read the article here)

Social cohesion in China, Wu says, is a rich research topic requiring interdisciplinary study with countless avenues still to explore and many implications for China’s sustainable development in the future. “Social cohesion is actually a power of consensus. Solidarity is representative of the soft power in society. The long-term practice of building social cohesion in China provides substantial evidence and experience for further research.”

Staying Ahead of Social Change

Looking to the future, Wu said he hoped that he and his colleagues might be able to stay on the cutting edge of social science research, spotting societal trends and proposing solutions before they become intractable problems. “Researchers should not be following right behind social reality, but instead stay one step ahead of it. If the society already is faced with some problem, any relevant study conducted at this time will lack preparation and quality,” Wu says.

Wu will not be alone in his pursuit. Over the years, he has been able to train dozens of graduate students who are now faculty members of top universities and institutes across China. "I am excited to return to such a vital research community here in mainland China," says Wu, who has already begun working with a new generation of sociology PhD students at NYU Shanghai. “I have a special attachment to Shanghai, a place I’d like to call home. This city will always be central to my research.”