NYU Shanghai’s Center for Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Culture welcomed science fiction writer and scholar Regina Kanyu Wang on February 25 to explore how Chinese female and nonbinary science fiction writers are pushing the boundaries of the genre, but also reimagining the zero-sum-game model of human-nature interactions that many sci-fi classics rely on.

Wang, a five-time Chinese Nebula Award (全球华语科幻星云奖) winner who is also an Applied Imagination Fellow at Arizona State University and Ph.D. candidate at the CoFUTURES project at the University of Oslo (Norway), shared the variety of literary, academic and pop culture influences that have driven the turn toward “ecological” themes in both her own work and in many corners of the Chinese sci-fi scene. Influenced by ideas surrounding climate change and the Anthropocene, many authors are exploring how non-human beings – from AI to plants, animals, and even fungi – might think and feel about global environmental change and the humans who are spurring those changes. But instead of sticking with an “us vs. them” mentality, these authors are imagining hybridized human and non-human beings to illustrate futures where people, technology, and nature collaborate and unite.

“In many writings in Chinese science fiction, especially in women's writing, there isn't such a clear binary thinking,” Wang said. “Instead, authors are writing about how different powers and different beings collaborate with each other and try to reach a balance, so that there is no clear boundary between the living or non-living, between technology or nature, or between the machine or the organic.”

Wang linked this approach to growing interest in ancient Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoism, part of a global trend toward using indigenous knowledge systems as “new frameworks for thinking about how we can cope with issues in our current world.” Themes of non-human consciousness and human to non-human transformation abound in Chinese folklore, Wang said, pointing particularly to the well-known musings of Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi (4th century BCE) about the dream of the butterfly or the happiness of fish.

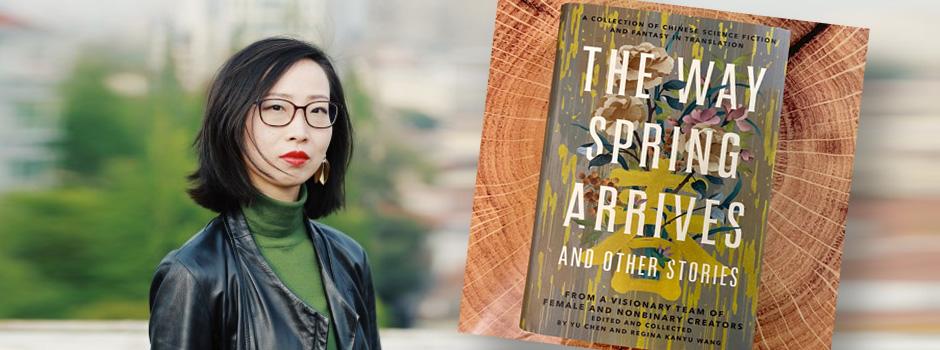

Wang is also the co-editor of The Way Spring Arrives, an anthology of new science fiction by Chinese female and non-binary writers and translators that will be released in English this month by U.S. fantasy and sci-fi publisher Tor Books. The collection’s title story by Wang Nuonuo, which uses the language of popular science to retell traditional Chinese myths of creator immortals, epitomizes the genre-bending tales by female authors that Wang says are pushing Chinese sci-fi – and its readers – into new intellectual territory.

“It challenges ideas of how we perceive climate change, and what is a season… It’s a good experiment with breaking out of our current understanding of mainstream, hardcore science fiction, and having a more playful and more vivid way of exploring … a larger world that is not yet framed by our current understanding of science and technology. But at the same time it shows how science and technology can serve as a way of reaching out to that larger world,” Wang said.

Wang joined Konior and an on-campus audience via Zoom.

Referring back to the work of Chinese feminist scholar Dai Jinhua, Wang said she sees this approach in current science fiction as a way to find contemporary meanings for Chinese traditional thought systems that leave room to consider gender, consciousness, and good and evil as attributes in a constant state of flux and recombination.

“Like yin and yang, these forces are not solid, and they are not hierarchical. Instead, they are always transforming each other and always interacting with each other,” Wang said.

Wang also branched out into a discussion of gender equity in Chinese science fiction, touching on the unique role that women have played in the scene since its earliest days in the late Qing dynasty, when one of Jules Verne’s primary translators was a female writer, Xue Shaohui. Despite many contemporary female sci-fi authors’ assertion that they have not experienced unequal treatment, Wang argued that China’s sci-fi scene still struggles with both the aggressively masculine legacy of Western sci-fi translations and lack of female representation in sci-fi fan and writers’ organizations.

Wang’s unique voice as a writer, scholar, and a historian of sci-fi is an important one in the study of human-technological interaction in contemporary China, said Assistant Arts Professor of Interactive Media Arts Bogna Konior, co-director of the Center for AI and Culture.

“The Center is interested in grasping the trends in contemporary discussions around technology and its social impact here in China, and we have found that science fiction is often where the discussion about cultural context, tradition’s role in the future, and the social impact of technology happens most explicitly,” said Konior. “Chinese sci-fi specifically needs to be part of the conversation about AI because China is leading in the implementation of emerging technologies.”