How can we explain worsening attitudes toward China in many corners of the globe? What concepts, ideas, and events form the basis for this declining public approval? And have China’s efforts to project soft power been effective?

Some 200 participants from around the globe gathered online on Feb 27 to grapple with these complex questions in the NYU Shanghai Provostial Distinguished Lecture by Xie Yu, Bert G. Kerstetter '66 University Professor of Sociology at Princeton University.

Xie’s talk, “Global Attitudes towards China: Social Facts and Interpretations,” focused on research methodology and preliminary findings for four projects examining how social identity, economics, media representation, and even the severity of localized COVID-19 outbreaks have interacted to create public opinion data that Xie termed “shocking and worrisome.”

Xie, whose prior research focuses primarily on social stratification, first became interested in understanding the roots of attitudes toward China in 2017, when it became clear to him that public opinion of China in the United States (and in several other countries around the world) had taken a sharply negative turn.

“Whether you like it or not, attitude is real and attitude has real consequences,” Xie said. “In today’s information age, public opinion will likely play an increasingly important role in foreign policymaking, because people express their opinions on the Internet, and their opinions affect policymaking.”

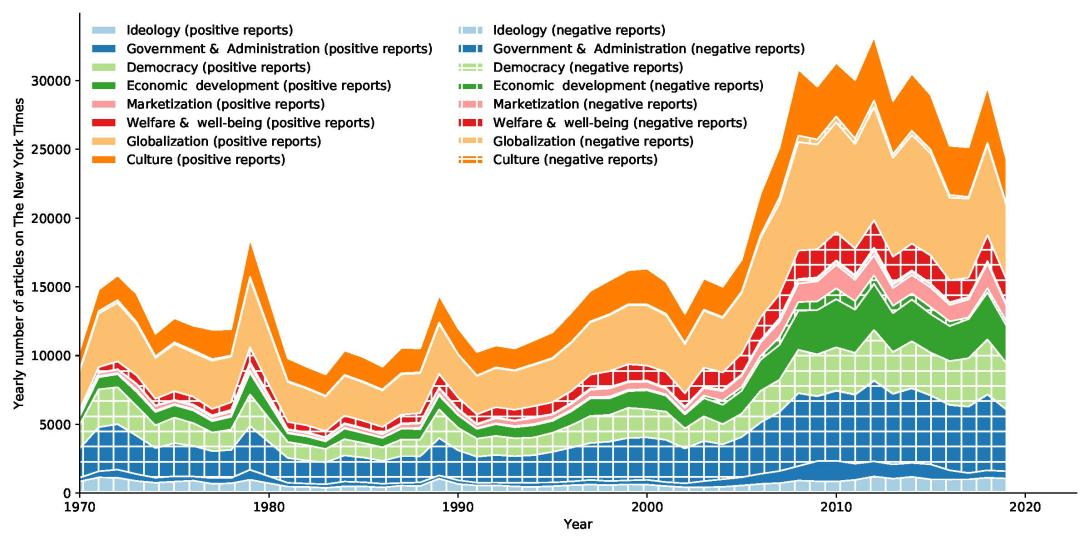

Title image: Charting positive and negative coverage of China in the New York Times across eight topical categories and almost 50 years. (Chart by Huang Junming, Gavin Cook, and Xie Yu.)

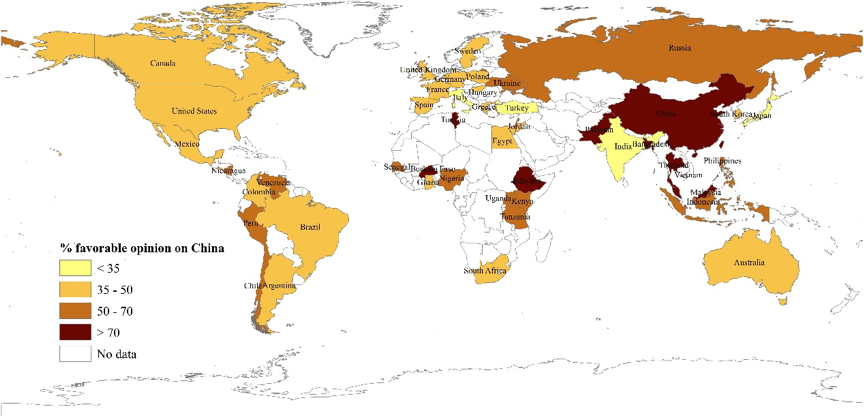

Country-level public approval of China has fallen to surprisingly low levels in many parts of the world. (Source: "Global Attitudes and Trends, 2014-2018," Pew Research Foundation. Map by Jin Yongai and Xie Yu.)

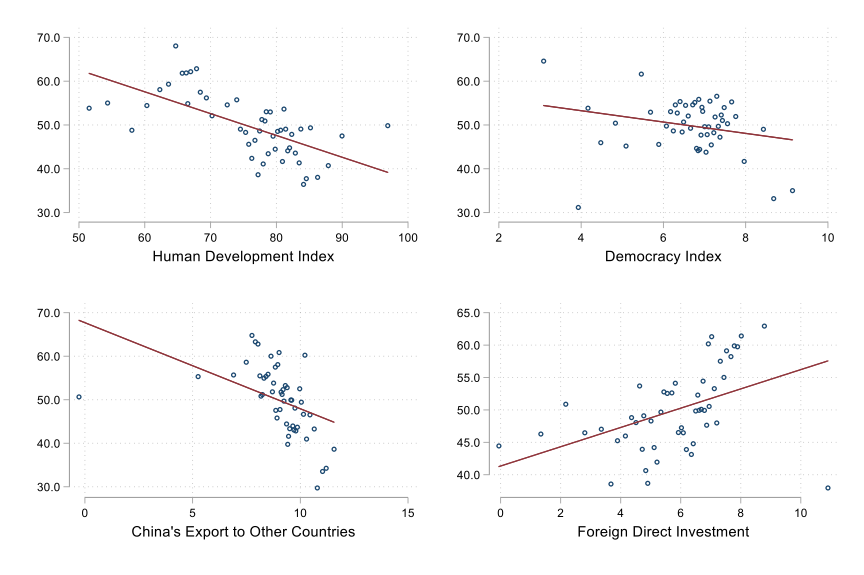

Using data from international research institutions on both sides of the Pacific, Xie and coauthors in both the U.S. and China were able to show that positive sentiment toward China has indeed been rapidly declining in many countries throughout the world over the past 15 years. Downward trends were especially pronounced in developed countries that rank highly in the Democracy Index, and in countries which are not recipients of Chinese foreign direct investment.

When Xie and fellow researchers compared U.S. public opinion of China to Chinese public opinion of the U.S. at the level of individual survey respondents, they also found that variance in opinions was often tied to individual education level and the kinds of news media topics that respondents said they “followed.” Although many U.S. respondents indicated positive views of China’s economic development and culture, the same respondents simultaneously indicated stronger negative views toward China’s system of governance.

Decline in public opinion of China correlates positively with countries' Democracy Index, Human Development Index, and exports from China, while the correlation is negative with Chinese Foreign Direct Investment. (Charts by Jin Yongai and Xie Yu, forthcoming in "Global Attitudes towards China: Trends and Correlates," Journal of Contemporary China.)

In a deeper dive into which factors associated with contemporary China have the greatest influence on U.S. public opinion of the country, Xie and fellow researchers at Princeton also studied how reporting on China in the New York Times correlates with broader shifts in American public opinion since the 1970s.

The team analyzed over 250,000 New York Times articles spanning the past five decades, using artificial intelligence to sort coverage into one of eight topical categories and to label coverage as either positive or negative. In the end, Xie and his coauthors found that roughly half of all fluctuation in U.S. public opinion of China was tied to one of two types of coverage: positive coverage of Chinese culture and negative coverage of democracy in China.

Xie says these findings seem to indicate that concerns about governance style and social values could be behind the dip in global attitudes toward China in countries with already high levels of economic development.

“A good starting point to enhance China’s global image is to understand the social facts of public opinion, to understand what other countries think of China and why,” said Xie. “The decline in attitudes toward China shows that China needs to institute radical changes, domestic as well as international, to improve its global image.”

Xie and fellow researchers also attempted to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. public opinion of China, despite somewhat limited data. Data comparing local COVID-19 infection rates with differences in levels of trust expressed towards Chinese people showed that individuals in areas with high rates of COVID-19 community spread tended to adopt more negative views of Chinese people in mid-2020. Xie cautioned that although this investigation’s results are not yet complete, the overall pattern emerging from the data bodes poorly for both China-U.S. relations and inter-ethnic relations involving Asian Americans in the United States.

Additional future directions for Xie’s research include a comparative study of social media’s influence on public opinion that will encompass millions of posts from Twitter and Weibo. More data and information on additional research directions is also available on the project website attitudetowardchina.com.

Xie’s lecture was jointly hosted by the NYU Shanghai Office of the Provost and NYU Shanghai’s Center for Applied Social and Economic Research (CASER).