Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Yifei Li grew up in two very different Shanghais: one, his family’s apartment on neon-lit East Nanjing Road, the other the city’s rural outskirts, where he caught butterflies and frogs with his father in a then largely-undeveloped Pudong.

Graduate studies in the largely-rural US state of Wisconsin led Li away from his preoccupation with urbanism to a more nuanced view of “the myriad ecological connections between urban centers and their hinterlands.” As a sociologist who has spent years working day-to-day with environmental officials and actors all over China, Li has had a first-hand look at how China’s rapid industrialization and equally rapid tide of “green” policymaking are completely reshaping landscapes and lives across the country, as well as around the world.

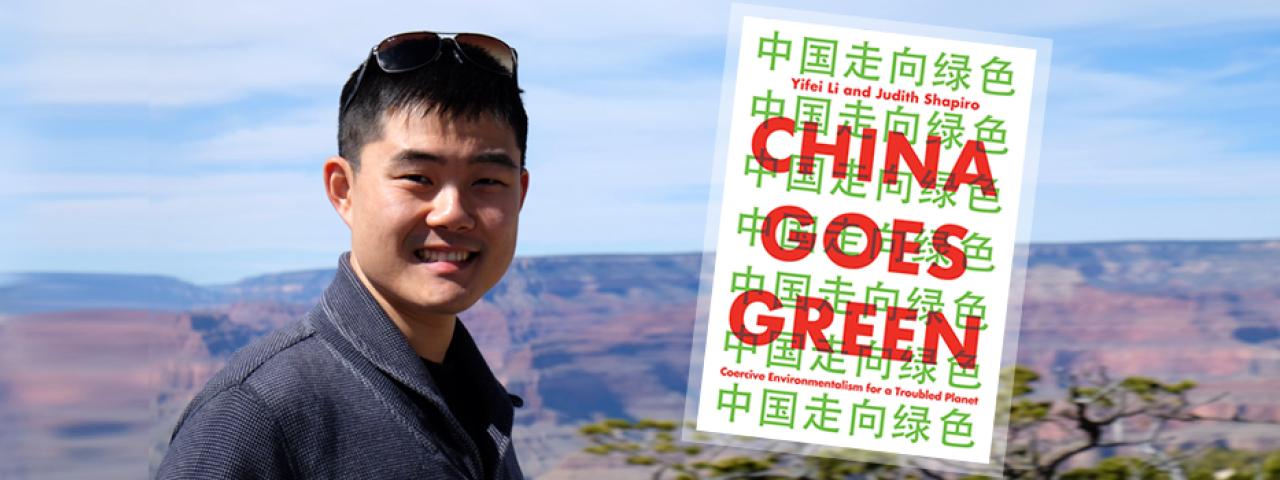

In the new book China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet, Li and his co-author Judith Shapiro of American University look closely at the promises and the substantial risks of China’s use of decisive, centralized state power to achieve environmental ends.

What inspired you to write China Goes Green?

Back when I was in graduate school, I read this book called The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future by historians Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway. It was meant to be a semi-fictional book, where they were describing the planet from the perspective of a future historian after “the Great Collapse of 2093.” They ended the book by saying that the West has ended, but welcome to the Second People's Republic of China. The idea was that China's decisive environmentalist moves were the only reason that China survived this global collapse, but the West didn’t. And I was just so struck by that.

I thought that it seemed really premature to unthinkingly embrace China as an example of how we should weather through the current climate predicament into the future. So for years, I was thinking about how I could go about proving that point false, or at least qualifying that point.

China is explicitly establishing green policies not only domestically, but also across a lot of other regions and on a lot of different scales. The environmental gains of these policies are observable and verifiable in some cases, but not in all. In fact, in some cases we have verifiable negative environmental consequences.

So in China Goes Green, we try to understand what exactly are the conditions that enable decisive state leadership in China to achieve good environmental outcomes, and also, what are the conditions under which decisive state leadership turned out not to work the way it wanted to, or the way it claimed to.

That’s a huge question! How did you go about finding an answer?

The book is premised on many, many case studies from all over China, all over the world, and even in outer space. Our sources are environmental officials, journalists, scientists and even individual garbage collectors in the city of Shanghai.

I just love talking to people, so sometimes I would see recyclers with their flatbed tricycles sitting on the street finishing a bun, and I would just sit next to them and say, “Hey!” I gathered a ton of information and got to know a lot of people that way.

And so many officials and scientists invited me into their offices and shared with me candidly about what they do, and what they think is valuable about what they do. Getting to know all these people has made me so much more sensitive to why environmental problems are so complex. There is no silver bullet. What solutions China has found are the result of very hard work by tens of thousands of real women and men in this country.

One of the flatbed tricycles that can be seen hauling recyclable waste all over Shanghai. Photo by Yifei Li.

Did you say outer space? What kind of environmental policies is China enacting in outer space?

In their plans for the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese official sources have included plans for this Space Belt and Road, which essentially describes a path of connectivity between the Moon and the Earth, especially talking about mineral deposits on the far side of the moon. Obviously that’s one case study site that [my co-author] Judy and I could not visit! [laughs]

This plan to mine the moon is so interesting, but also so risky in every imaginable way. At the same time, we live in a world where countries are competing for resources in outer space. Russia just claimed sovereignty over Venus, and Trump has established this space arm of the US Defense Department, which is getting huge federal subsidies to do research into outer space.

So given the level of commitment on the part of these major players in this field, we felt it had to be included in the book.

So, back to the case studies. What did your case studies reveal about what’s working and what isn’t working as China “goes green”?

One of the arguments that we tried to stress in the book is that we need to fully revive a system that China already has, which is this political consultation mechanism. Consultation with people from all walks of life is an integral part of the Party’s political apparatus – it’s actually written into the Constitution.

A lot of the environmental science literature that looks to China’s example of centralized policymaking and implementation is saying that we need quick and decisive action, whatever works, to solve the climate crisis. But precisely because we need all the help we can get, we can’t rely on just the government itself. Everybody should have the space to contribute.

The notion of ecological civilization has tremendous potential. But it takes science - independent scientific work - to inform policymaking, and it also takes environmental journalists, environmental lawyers, and a lot of citizen groups. There are great examples of where China’s green policies are working, and one thing that those examples share is that the government opened more channels to bring useful inputs from the public and from experts into the policymaking process.

Can you share a couple of examples from the book? Where can we look for models of Chinese environmental policymaking that have gone right?

The rehabilitation of the Loess Plateau is one of the most impressive ecological rehabilitation projects anywhere in the world, not just in China. I think one of the main reasons why is that a group of experts from various backgrounds – national development specialists, ecologists, urbanists, community development specialists, sociologists – all worked together, and for two years all they did was interview community members.

They went from village to village, settlement to settlement, to learn the local ways of life - not only their current ways of life, but also what local people did 20, 30, 50, 100 years ago. So I think it's that level of commitment to deep-learning the knowledge and strategies that communities have accumulated over the course of many, many decades that really enabled this group of scholars to put together a very solid plan. And once the plan came together, the community loved it, and it made scientific sense, ecologically and sociologically, and economically, too. It's examples like this that give us a lot of hope about what China could accomplish.

A landscape in Datong, Shanxi that is typical of China’s arid Loess Plateau. The region has suffered from over a century of desertification, but Li and Shapiro highlight a project to reintroduce polycultural forests to the region as one of the best examples of Chinese green policy done right. Photo by Till Niermann, via Wikimedia Commons.

You mentioned one of your sources being Shanghai garbage collectors. Is there a case study site in Shanghai that interested students and NYU Shanghai community members could visit to understand some of the points you raise in China Goes Green?

There's a recyclable collection center near campus at the northwest corner of the Yuanshen Lu and Weifang Lu intersection, and a lot of recyclers hang out there. Many of them are couples or families, and they are all very friendly, in my experience. More importantly, they have tons of stories to share about their lives and jobs in this city of neon lights, which so often neglects their presence.

A lot of NYU Shanghai students actually played a really important role in creating the book, especially Isabella Baranyk ’18, Bo Donners ’18, Yuan Qianchun ’20, and Tian Tian Wedgwood Young ’20. I sometimes say it takes a village to write a book, and in my case, this village is called NYU Shanghai. I just can't imagine a university that is more diverse and vibrant than what we have here, but what draws everybody together really is a commitment to understanding China, and this is just tremendously valuable. I always think of this building as a community of thinkers who come together because we love to think, we love to debate, and we love to have good conversations.

Read more about China Goes Green in The Economist and China Dialogue, or check out the book at Amazon, Book Depository, or your local retailer. China Goes Green is published by Polity.